by Elisabeth Paul

Overview

Animal blood has a long culinary history throughout Europe, though recently has become neglected. We are interested in (re)valorising the despised and forgotten, so we had to look deeper into what blood is, how it should be handled, and what to use it for. Its coagulating properties led us to focus on blood as an egg-substitute in sweet products, since egg intolerance is one of the major food allergies affecting children in Europe.

In fact, eggs and blood show similar protein compositions, particularly with the albumin that gives both their coagulant properties. Based on these similarities, a substitution ratio of 65g of blood for one egg (approx. 58g), or 43g of blood for one egg white (approx. 33g) can be used in the kitchen. Using this method, we have developed recipes for sourdough-blood pancakes, blood ice cream, blood meringues, and ‘chocolate’ blood sponge cake.

A further benefit of blood is its ability to prevent anaemia – the most common micronutrient deficiency worldwide – due to the high bioavailability of its haeme-iron. This iron, of course, is often the challenging factor for taste, which in many cultures have traditionally alleviated by pairing with it strong flavours such as herbs and spices. We investigated some of these traditional pairings as well as some newer ones including woodruff and roasted koji.

During sensory evaluation, we were surprised at the variation in perception of the bloody aftertaste, which led us to an interesting discussion on the relationships between gender, age, and taste.

Blood for most is not a go-to ingredient. It has become somehow ‘edgy’, almost forbidden; yet it has been used as food for as long as animals have been killed and eaten. It is elemental, both mystical and mundane. And it makes us damn curious in the kitchen.

Blood is a brute fact of killing animals. A slaughtered pig can yield between 2.25 and 4.5 kg of the stuff,[1] which adds up quickly. We are always searching for deliciousness in the ignored and overlooked, so the question arose: how can we transmute this substance into an ingredient fit to celebrate? And then, more specifically: could blood be a substitute for eggs, especially in pastry, given that egg white intolerance is Europe’s second largest food allergy?[2]

Even just decades ago, blood was appreciated as a source of nutriment and unique taste – appearing in an indescribable variety of blood puddings, blood sausages, blood desserts and blood pancakes throughout the Europe and Asia. Why is the tradition of cooking with blood disappearing from our kitchen? One answer might be the disappearing knowledge on how to process it – and with this disappearing knowledge comes insecurity for those who are trying to preserve and rediscover it.

Where does it all go?

By far most blood from pigs (around 70%)[3] is separated into plasma and serum used in animal feed, pharmaceutics, cosmetics, and commercial products like cigarette filters. Dried blood is used as fish food or fertilizer. Red blood cells are used for mink feed. Meat glue, or transglutaminase, is used to make novel forms of meat, like imitation crab, or to bind cuts in hams[4] – and in fact is an enzyme extracted from blood, originally responsible for clotting by stabilizing the protein fibrin.[5]

Composition

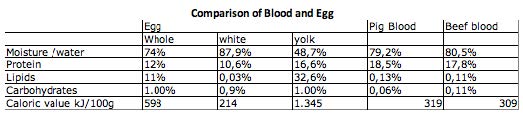

Though the bloods of different mammal species are similar in composition, the amount of blood obtained per animal varies greatly. In pigs, for example, blood makes up around 3.3% of live weight, which generally yields about 2.5L per animal.

Blood is a homogenous mixture of blood cells and serum. The serum (55%) is mainly composed of water (80%) and proteins (17%) such as albumin, fibrinogen and globulin, as well as glucose, minerals and hormones.[6]

Serum albumin is the most abundant and important protein in the serum, at around 50% of total protein content. This places it at a similar level to ovalbumin in eggs, around 60% of total protein content – which means in the kitchen, it provides an optimal replacement due to its foaming ability.[5]

There are three types of blood cells suspended in the serum: white blood cells; platelets or thrombocytes; and red blood cells which contain most of the haemoglobin, a iron-bound protein that is responsible for the red colour. Colour changes depend on reactions of these iron ions, regulated by storage conditions, oxygen availability, and temperature, and are similar to the colour changes that happen with meat. Vacuum-packed, blood is dark, close to purple; left outside for a while or whipped into foam, it turns bright red; and heat treatment leading to protein denaturation gives it a dark-chocolate brown, nearly black appearance.

Blood Clotting

Once the animal is slaughtered, blood platelets and plasma come into contact with other animal tissue, causing blood clotting. Due to the enzyme thrombin, the fibrinogen in the serum is transformed into fibrin, an insoluble protein forming strands. In these strands, big red blood cells get predominantly trapped, giving the intense dark colour from the haemoglobin contained therein.[5]

There are several anticoagulants that can be added to prevent this process. Generally calcium ion binding salts such as citrates and phosphates are used in slaughterhouses to prevent clotting. Traditionally, a metal spoon would be used, with constant stirring. If calcium ions are bound, no available calcium means no clotting.

Important: shake blood regularly before use, and strain.

Blood as substitution for eggs

One great argument for blood as an egg-substitute is the increasing food allergy for egg proteins, nowadays second-most prevalent food allergy in Europe, affecting mainly children but also adults. In Germany, for example, 8% of children have temporary reactions to egg. Other sources estimate that 30-53% of children with food allergies in European countries like Spain and France are allergic to ovalbumin.[2]

Blood shows a similar protein composition to egg, yet with slightly different types of proteins. The serum albumin, as the main constituent of blood protein with 55%[4] is tolerated whereas ovalbumin in egg white leads to heavy allergic reactions. But perhaps the greatest argument for cooking more with blood is to alleviate iron deficiency, which causes anaemia – the world’s most common micronutrient deficiency.[7] And the haeme-iron in blood, in turns out, is the best possible source for the human body, showing a 2- to 7-fold bioavailabilty in comparison to non-haeme iron.[8]

Cooking properties of blood

The texture in blood pastries in comparison to egg-pastries is intriguingly similar. When whipping blood, more time and stepwise increase in speed is required, similar to methods for producing a very stable, fine-beaten egg white.

Coagulation due to heat treatment occurs between 63°C – 75°C. Heat denaturation of serum albumin requires a temperature of 75°C – at this temperature batters with blood will thicken. Egg coagulation, due to ovalbumin on the other hand, does not happen until 84.5°C. So less heat and hence less time is required when cooking with blood.

General substitution ratios:

1 egg (approx. 58 g/unit) = 65 g of blood

1 egg white (approx. 33 g/unit) = 43 g of blood

We have also observed interesting leavening properties in baking sourdough bread when sourdough starter is fed with blood instead of water for its final feeding. Volume nearly doubled in less than 1 hour, turning the bread dough dark-chocolate brown and changing the flavour profile of the bread to a richer, mildly acidic, moist bread. This discovery is still preliminary, and more culinary research is needed on blood and sourdough.

Hiding the animal – masking aromatic agents

Eugenol and cinnamaldehyde are classic aromatic compounds that are found in traditional recipes in combination with blood. In tasting panels done with blood meringues (recipe below) cinnamon and clove expectedly scored low in bloody aftertaste, but new combinations involving roasted barley koji and woodruff also showed promise.

Another good combination appears to be blood and acid, as tried in the sourdough blood pancake recipe. One possible reason could be due to the similarity of stimuli for acidic and metallic receptors on the tongue, both being sensed through ion channels, but we have found no research on this subject.

Due to sometimes intense and unexpected responses from taste testers, the question arose whether metallic taste and/or animal notes would be perceived differently according to gender and age.

We discovered that taste perception in general differs between male and female tasters, and younger and more elderly, with women generally having an increased sensitivity towards metallic taste.[9] Perception thresholds for bitter and sweet compounds vary not only between the sexes, but also with monthly-changing hormone concentrations in women that influence their nervous system.[10] Decreasing thresholds during menstruation means that women will perceive bitter compounds more easily at these times. Unfortunately no research has been done on changes in metallic taste-perception during the menstrual cycle, since metallic taste via ion-channels is a rather young discovery. During our own tests of our blood pastry products, however, this difference became obvious to us.

Animal aromas exhibit similar properties. Olfactory stimuli are translated in the central nervous system, and stimulation can be altered with changing hormone concentrations.[8] Women are thus generally more sensitive to androstenone and skatole (two animalic odours occurring in entire male pigs) than men, and might therefore show lower preference for blood containing products from entire pigs.[11] This may be the case even though skatole and androstenone are ten times more concentrated in the fat than other tissues or blood. More research needs to be conducted on the subject.[12]

Recipes

Using blood in the kitchen drove us to the edge:

blood with sourdough,

blood as sourdough feed,

blood in kefir-culture (not recommendable),

blood in alcohol creating the Red Russian (in vodka, after filtering the denatured fibrin clots – only sipped once).

Here are some recipes that can be and have been eaten with a clear conscience.

Blood ice cream (for 1 paco container – 12 servings)

This recipe is inspired by traditional Italian dessert variations called sanguinaccio.[13]Given that cocoa doesn’t grow here in the north, we have run our trials with roasted barley koji, which is a brilliant alternative and ingredient in its own right – especially in combination with blood, giving body, bittersweet complexity and increasing the malty notes of the moulded, toasted grain taste.

300 ml pig blood (318 g)

60 g roasted Koji

300 g milk 3.5% fat (it may need around 200 ml extra, depending on the fineness and absorption capacities of the grain)

200 g cream (38% fat)

88 g trimoline (or 11% of ice cream mixture)

2.8 g guar gum (or 0.3% of rest of ice cream mixture including trimoline)

The day before:

Grind roasted koji to fine powder and cold-infuse it into 300 ml of milk. Leave at 4°C for 24h.

Production day:

Pass cold infusion through a super bag and measure yield. Add more whole milk to reach weight of 300 g.

Strain pig blood to remove coagulated protein clumps.

Add cream, blood and trimoline to mixture and start to heat over water bath while stirring constantly. Once temperature reaches 50°C, add guar gum and continue stirring until mixture thickens to chocolate brown custard. Heat until 75°C and hold at temperature for 15 seconds. Fill pacojet container and freeze.

Once frozen, spin in pacojet and serve.

Sourdough blood pancakes

Swedish blodplättar and Finnish veriohukainen are traditional variations of blood pancakes, and provided an existing foundation to understand platelets’ culinary functionality. In fact, the name blodplättar itself translates directly as ‘platelets’. The acidity of the sourdough starter is a great aid to soften the metallic aftertaste of the blood.

Basic recipe for fluffy pancakes.

235 ml of rye sourdough starter

150 ml of pig blood

30 g of melted butter

50 g of granulated sugar

Strain pig blood to remove blood clots.

Add sugar to blood and whisk in Kmix/Kitchenaid. Increase speed gradually until mixture is stiff.

Mix sourdough starter with melted butter, fold in 1/3 of blood foam, and add the rest once it becomes a homogenous batter. Bake in pan in abundant butter until dark chocolate colour.

Caution: easy to burn due to similar colour range of batter and burned pancake.

Blood Meringue

Blood as egg substitute in meringue seems difficult texture-wise at first, but once the whipped blood and sugar form this magnificent foam, all doubts are cleared. Probably one of the strangest textures Nordic Food Lab has seen, and one of the most beautiful. Definitely room for further investigations. We also want to note that this one was inspired by the pig’s blood macaron from Mugaritz in Spain. So delicious.

Trials have been done with both the French and Italian meringue methods (Harold McGee divides them into uncooked and cooked)[14]. Preferable for blood seems to be the uncooked method, since the meringues are perceived as less animal in flavour to the tasting panel.

70 g pig blood

30 g of granulated sugar

30 g of icing sugar

Flavour variations used:

2 pinches of Long pepper and salt, ground or

2 pinches of cinnamon, ground or

3 pinches of woodruff, dried and ground

Pour blood and granulated sugar into a kmix/kitchenaid and start mixing at low speed. Gradually increase speed up to level 5-6 once sugar is dissolved. Add icing

sugar to the whipping blood, and make sure nothing sticks to the wall. Season blood mixture when it is glossy, bright red, and very stiff.

Fill in piping bag, place meringue on baking mats and dry at 93°C at very low ventilation level (level 2 on Combi Rationale oven) until dry and dark chocolate brown.

Sponge Cake – Basic recipe without egg

How to bake a classic black forest cake without egg – an adaptation of the Larousse recipe.

230 g pig blood

100 g granulated sugar

25 g wheat flour

25 g corn starch

25 g cocoa or roasted koji, ground (Koji recipe see blogpost je)

Sieve flour, starch and koji twice to obtain a homogenous mixture. Mix blood very slowly in Kmix/Kitchenaid gradually adding sugar. Once dissolved increase speed to level 6-7 and whip until stiff. Pour in flour-mixture and lower speed to minimum, incorporating flour into blood mixture without volume loss.

Fill in spring form and bake at 180°C for 25 minutes. Test the cake by touching the surface – when it makes a crackling sound the cake is ready.

If you make two, you can use them as the base for a classic black forest cake. Or in this case, a not-so-classic blood forest cake.

As with all the other recipes, taste testing was of utmost importance. I made two half-cakes: one with blood, the other a chocolate control. Both were delicious.

It may seem excessive, but I’m German and cake-making is in my blood.

Best Practices when handling blood

1. Best source is your butcher of confidence. Ask him where the blood is from, when the pig was killed and how the blood was treated (with anticoagulants)

2. Smell it! It should have a sweet, rich, metallic odour without strong animal flavours. Strong aromatic changes can occur in un-castrated pigs due to their production of skatole and androstenone.

3. Respect cold chain throughout the handling (2 – 4 degrees) and use within a week when refrigerated.

4. Shake and strain before use.

5. Freeze for longer storage. The colour becomes darker. Thaw blood on the same day as processing.

The approximately 8 L of pig blood that have been used during the experimentation came from 3 free-range pigs, raised and slaughtered at Grambogård Slagteri, a slaughterhouse with high animal welfare standards in Funen, Denmark.

References

[1] McLagan, J. (2008). Odd Bits – How to cook the rest of the animal. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley: pp 223-225

[2] Food Allergy Research and Education (http://www.food-allergens.de/symposium-vol1(1)/data/egg-white/eggwhite-data.htm)

[3] Yun-Hwa Peggy Hsieh and Jack Appiah Ofori (2011). Food-Grade Proteins from Animal By-Products: Their Usage and Detection Methods. Handbook of Analysis of Edible Animal By-Products. Editors Nollet, L., Toldrá, F. CRC Press, New York.

[4] Motoki, M., Seguro, K. (1998). Transglutaminase and its use for food processing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 9, pp 204

[5] Griffin, M. et al. (2002). Trandsglutaminase : Nature’s biological glues. Biochem. Journal 368. pp 377-396

[6] Belitz, H.-D., Grosch, W., Schieberle, P. (2009). Food Chemistry – 4th revised and extended Edition. Springer Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 594-595

[7] Nollet, L.M.L., Toldrá, F. (2011). Handbook of Analysis of Edible Animal By-Products. CRC Press, New York, 16-20.

[8] EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS)(2010). Scientific Opinion on the safety of heme iron (blood peptonates) for the proposed uses as a source of iron added for nutritional purposes to foods for the general population, including food supplements. EFSA Journal 2010; 8(4):1585. [31 pp.].

[9] Gandelmann, R. (1982). Gonadal Hormones and Sensory Function. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 7, 1-17.

[10] Brown Parlee, M. (1983). Menstrual Rythms in Sensory Processes: A Review of Fluctuations in Vision, Olfaction, Audition, Taste and Touch. Psychological Bulletin 93 No.3, 539 – 548.

[11] Font-i-Furnols, M. (2012). Consumer studies on sensory acceptability of boar taint: A review. Meat Science 92 Issue 4, 319-329.

[12] Chen, G., Zamaratskaia, G., Andersson, H. K., & Lundström, K. (2007). Effects of raw potato starch and live weight on fat and plasma skatole, indole and androstenone levels measured by different methods in entire male pigs. Food Chemistry, 101, 439–448

[13] McLagan, J. (2008). Odd Bits – How to cook the rest of the animal. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley: pp 223-225

[14] McGee, H. (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, New York.

[15] Calory Lab, accessed 23rd august http://calorielab.com/foods/eggs/39