by Ben Reade.

This paper was first published in ‘Wrapped and Stuffed: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012′. The complete Proceedings is available from Prospect Books; a video recording of the presentation of this paper can be found here (starting at 33 minutes), and a podcast about it here.

People dig for peat. Once dry, this peat burns hot and lets off an evocative smoke that brings to mind the cooking and heating methods of yesteryear. The peat-cutters harvest their quarry from dark brown, water-logged quagmires. Occasionally, these accidental archeologists discover artifacts left by people long gone. One such artifact, among the most commonly unearthed items from the watery, misty bogs of Ireland and Scotland, is known as ‘bog butter’. Due to the frequency of these findings and its mysterious nature, it has been fairly well studied from an archaeological perspective, perhaps the most thorough investigation being that by Caroline Earwood (1). In this study I will attempt an exploration of the substance through the eye of a chef and gastronome, combining available literary evidence with our own practical research. We made our own bog butter and subsequent gastronomic analysis with the hope that a new gastronomic perspective on the topic would give us access to a more pragmatic understanding of how and why ancient peoples buried their butter.

Bog butter is butter that has been buried in a peat bog (2). It has occasionally been confused with animal adipose tissue (most commonly sheep tallow), which has been preserved in the same manner. Over 430 instances of bog butter have been recorded (3). Of these, 274 have been found in Scotland and Ireland since 1817. These samples are well catalogued by Caroline Earwood. The earliest discoveries are thought to come from the Middle Iron Age (400-350 BC), though this does not exclude the possibility of much more ancient roots. More recently one firsthand account tells of butter being buried for preservation in Co. Donegal 1850-60 (4). In 1892, Rev. James O’Laverty, an advocate of the argument that the butter was buried for gastronomic reasons, dug some butter into a ‘bog bank’ and left it for eight months. His experiment was carried out in much the same spirit as ours – for analytical purposes and not for a cultural or preserving motive (5).

This paper aims, by making bog butter using appropriately basic technology, to explore why the boutyrophagoi, or ‘butter-eaters’, across Scotland, Ireland, the Faeroe Islands, Finland and Norway, as well as Kashmir, Assam and Morocco have buried their butter, with special focus on the Irish, Scottish and Scandinavian traditions (6). The aim of this paper also extends to a discussion of whether or not butter preserved by this method can have a hedonic value for today’s palates, and possibly some use in contemporary cuisine.

Peat bogs are, by their nature, cold, wet places; almost no oxygen circulates in the millennia-old build-up of plant material, which creates highly acidic conditions (our site had a pH of 3.5). Sphagnum moss bogs have remarkable preservation properties, the mechanisms of which are poorly understood (7). Early food preservation methods have been researched extensively by Daniel C. Fisher, in relation to the preservation of meat. In an attempt to recreate techniques used by paleoamericans in North America, Fisher sunk various meats into a frozen pond and a peat bog. A key finding from his research is that after one year, bacterial counts on the submerged meats were comparable to control samples which had been left in a freezer for the same amount of time (8). In fact, suitable foods can probably be aged in many types of soil: salt-rich that will provide dehydration, very cold/freezing that will freeze foods or slow degradation, or, as in our case, anaerobic and acidic conditions to prevent microbial action and oxidation. To our canny ancestors, this preserving characteristic provided an ideal place to bury foods (9).

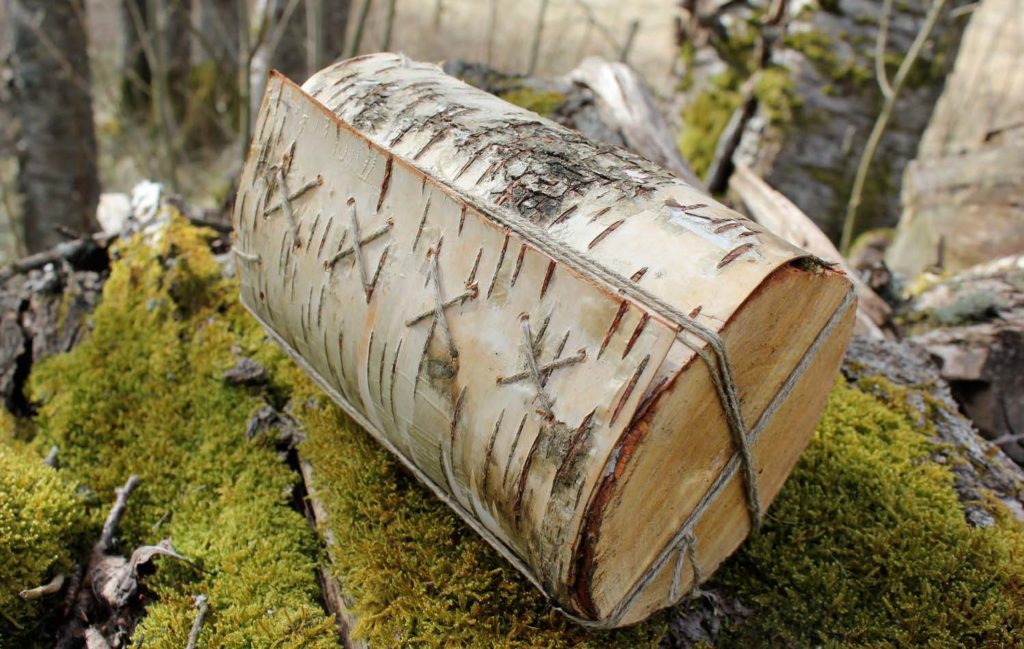

Around two thirds of the bog butter that has been discovered has come in a container or wrapping of some description. These containers are varied; during the spring and summer months when butter was abundant, dairymaids probably used almost anything they could for storage. The most common containers are wooden. These can be described under the broad classifications of kegs, churns, bowls, dishes, boxes, troughs, methers, firkins and piggins (10). The slowly evolving techniques of the artisan can be seen in these containers and until recently, dates were ascribed to archeological examples of bog butter in part on account of the workmanship of the container. Willow baskets, staved tubs, or bark wrappings have been used, as have bladders, intestines, and skins or woolen cloth (11).

Buried foods around the world

banana bread (Ethiopia, banana dough),

buried eggs (China, eggs),

davuke (Fiji, bread fruit);

formaggio di Fossa (Italy, cheese);

ghee (India, clarified butter);

gravadlax (Scandinavia, salmon);

gubenkraut (Austria, cabbage);

hákarl (Greenland, Greenland shark);

igunaq (Inuit Arctic, walrus);

kiviak (Greenland, auks in a seal skin):

lutefisk (Scandinavia, white fish);

muktuk (Alaska, seal flipper);

reindeer’s stomach (Sápmi, Sweden, stomach with contents);

rue tallow (Faroe Islands & Iceland, sheep’s tallow);

sealskin poke (Alaska, meat/dried fish with seal fat);

smen (Morocco, clarified butter);

surmjølk/myrmjølk (Norway, milk);

Many fermented foods are prepared in fully or partially buried amphoras, including wine in Armenia and soya sauce in Korea.

Sometimes a combination of materials has been used, such as bark with a bladder, or with a willow basket. One example used a barrel bound in a deerskin to stow the butter into its peaty hiding place (12). One particularly interesting find, discovered in Rosmoylan (Co. Roscommon, Ireland) dates from the late Iron Age. Within a two piece barrel, the butter was surrounded with plant fibers from sedge (Eriophphorum vaginatum), bent grass (Agrostis sp.) and the soft-textured moss, hypnum (Hypnum cupressiforme) (13). All three of these plants have a long history of being used by people in mattresses and bedding; the latter takes its name from the Greek ‘hypnos’ meaning ‘sleep’. It is rather poetic that dairymaids had thought of these plants as appropriate for protecting their butter. The butter was wrapped up and made comfortable before being laid down for a long sleep in the bog.

Butter and other dairy products were frequently used as a form of taxation and rent (14). At Naas Castle in Sweden where we conducted our experiment, butter was a form of tax from the construction of the castle in 1500 until the end of the nineteenth century. One early fifteenth-century manuscript from Scotland, by the Rev. Dr. Archibald Clerk, reports sixteen horse-loads of butter and cheese being found hidden or ‘laid-up’ near a tenant’s house (15). Butter is valuable: for that reason alone worth hiding, even more so in lawless times. One author gives testimony that treasures were buried inside fats, so when bog butter was discovered it was pierced from all directions to check for valuables (16).

Butter had many uses. It could be used for waterproofing fabric and also a dwelling – one bog house has been discovered where butter and sand have been mixed together to make watertight cement (17). It might also have been used as a light source. Angus Grant’s 1904 report tells that the found butter was converted into candles but as ‘the candles spluttered and crackled, sending sparks of boiling tallow all round…they were voted uncanny, and promptly got rid of’ (18). So while there are many suggestions as to why butter was buried, I propose it was buried not only for its obvious value as a commodity but also for some gastronomic purpose.

While being buried during times of plenty to keep for leaner times, the butter may also have increased its gastronomic value during its time underground. The fact that bog butter never contains salt suggests that it may have been buried to preserve it in times when salt was scarce (19). During the warmer summers, when rancidity would quickly take hold, burying may have not only been a convenient way of preserving butter but also of creating a luxury food (20). As the Danish priest and topographer L.J. Debes said of the Faroese hoards of buried tallow, ‘the longer it is kept being so much the better’ (21). O’Laverty wrote that the Irish buried their butter to ‘sweeten it’ (22). He also suggests that it was put into peat to mature it and render it more nutritive (23). This increased nutrition may be some kind of representation in popular memory of how stored butter could provide for lean times, though it may also refer to a palatable flavour or some biochemical change within the butter itself which renders it more nutritive. Testimonies of bog butter tasting tend not to describe it as rancid, but many liken the altered fat to cheese. I had to make some to see for myself.

The Experiment

From: The

Irish Hiudibras (24)

But let his faith be good or bad,

In his house great plenty had,

Of burnt oat-bread, and butter found,

With Garlick mixt, in boggy ground,

So strong, a dog, with help of wind,

By scenting out, with ease might find:

And this they call the bravest meat,

That hungry mortals e’er did eat.

So it happened I was introduced to Patrick Johansen, an artisanal butter producer from Sweden. When I heard of his interest in aged butters and experimental butter with wild bacteria, we got to talking. Soon afterward we set to work creating some bog butter of our own. Patrick lives surrounded by great swaths of Swedish forest where elegant birches and enormous oaks grow, interrupted only by the occasional lake and, conveniently, peat bog. His house is a long way from anyone or anything; the water supply is a well in the garden and the only light from paraffin lamps. Patrick learned to make world-class butter from his grandmother, who in turn had learned from the matriarchal line before her. My approach dictated that he decide how everything should be done with the only limitation being that no technology should be used that was not available before the industrial revolution.

On the snow-sprinkled morning of 8 April 2012 we embarked on making our twenty-first-century bog butter. We decided that birch bark was to be our material of choice for crafting containers in which to bury the butter. Using an old iron axe we brought down a smooth, tall, straight birch, the bark from which we swiftly peeled. Birch bark unwraps from the trunk with remarkable ease at this time of year; it is soft and pliable yet firm and strong. We peeled the bark and sliced sections out of slightly smaller parts of the tree to make tops and bottoms to our ‘barrels’.

We had decided we should make some smaller samples which could be dug up sooner, and then a larger one which will sit underground for some years. The Irish Hudibras (1689) asserts that in Ireland, ‘butter to eat with their hog, was seven years buried in a bog’ (25). Seven years seems an appropriate length of time for our butter to age.

Although the technology of butter making has changed through the years, the principles remain roughly the same. Butter is made by souring cream, which is then churned until it splits into its fat (butter) and aqueous (butter-milk) phases. The solid butter is removed from the liquid buttermilk, clumped together and washed by kneading it in clean cold water – this removes excess milk solids and buttermilk, thereby increasing the butter’s longevity. After washing until the water runs clear, the butter is thrown. This is a process of subjecting the butter to some high impact (literally throwing it against the table), which expels excess water. Now you have butter. The whole process with the latest technology takes about fifteen seconds – for us, it took a little longer.

In earlier times, after milk had been left to stand to allow the cream to rise, it would need to be filtered to remove insects and dirt. Patrick tells me this was often done through grass which, as well as filtering, also supplied the cream with ample lactic acid bacteria. The cow’s teat, dairymaid’s hands, wooden containers and tools would have also provided plentiful souring bacteria. Filtering could also have been done with a piece of cloth, the advantage being that at the end of the diary season the cloth could be dried out, preserving spore forming lactic acid bacteria to be rehydrated and used to inoculate the new batches the following dairy season (non-spore forming bacteria would be lost). For our experiment, in the absence of a cloth from the previous season, we chose to use a ‘nest’ of grass for filtering. Then the cream was left to sour in a small stone-walled hovel, sunken into the hillside; the kind of dwelling that early pastoralists might have used while in summer pastures.

After souring, the cream must be churned. Traditionally this might have been done by filling a calf’s skin with the soured cream and hanging it from a wooden tripod or tree. The skin could then be swung back and forth until the cream split. Many bog butter samples contain large quantities of cow hair, suggesting that perhaps this method of swinging and shaking in a cow skin was often used (26). To avoid problems of cow hair and in the absence of a calf’s skin, we churned our cream by shaking it in a large jar.

The butter was then washed to remove the majority of butter milk. We did this with fresh cold water from the well in the garden – this is quite a simple process of allowing water soluble parts to be washed out of the butter. Then we removed a large amount of the water by repeatedly picking up the lump of churned and washed butter and throwing it down onto the table. Throwing is an important step in the production of butter to be preserved, so we made sure to do it thoroughly.

We had made four small containers from birch bark and one from pine bark, and we also adapted a large old willow basket to hold a larger sample. In echo of the Rosmoylan bog butter discovery mentioned above we wrapped the butter in hypnum moss, before stuffing these moss-swaddled cylinders into our birch bark barrels – a comfortable bed in which our butter could sleep. Our willow basket held a half-firkin (approx. 12.5 kg) of butter, which was wrapped in a linen apron before being placed in the basket. It was important, as with historical bog butter finds, that the upper surface of the butter be entirely convex, in order that no water collect and stagnate on the top.

Downey et al. note that a large percentage of bog butter discoveries have been made along historic boundary lines (27). In 1892, James O’Laverty wrote that the butter was dug into ‘bog-banks’, perhaps another type of territorial confine (28). Debes’s 1673 description of the Faroe Islands describes how the preserved tallow or ‘rue tallow’ was buried in a ‘dike’ which certainly hints at a wall or embankment of some kind (29). There are many reasons why this should be the case, though it has largely been attributed to ritualistic motivations. I would suggest it may also have been to leave the food in a spot where people were unlikely to dig, and where there was a clear landmark. After looking for an appropriate bog to dig in we found a spot in a sphagnum and birch tree bog. The ground was soft enough to dig easily, and the holes slowly filled up with acidic bog water. We divided our containers between two holes and buried them at around 100cm below the surface. One of these stashes was unearthed and tasted three months after its burial (some notes on these tastings are found below). The second hoard will be allowed to age for a longer time, for seven years in echo of The Irish Hudibras, or perhaps left forever as some confusing archeology for the future: ‘It may, therefore, be termed a hidden treasure, which rust doth not consume, nor thieves steel away’, as Debes wrote in 1673 (30).

Finally, after counting our steps back to the path, we took a corner off a large rock with the back of our axe. This palm-of-your-hand-sized chunk of rock will now serve as a key. For whoever returns to dig up the butter, the stone key will fit into the rock and the butter will rise up from the bog.

The Results

At this point in time, five of our buried containers have been unearthed and tasted, and one remains in its peaty wallow. Tastings of three-month-aged bog butter have been made at both Nordic Food Lab in Copenhagen, Denmark and at the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012 in Oxford, England. Various conclusions can be drawn from these tastings.

In its time underground the butter did not go rancid, as one would expect butter of the same quality to do in a fridge over the same time. The organoleptic qualities of this product were too many surprising, causing disgust in some and enjoyment in others. The fat absorbs a considerable amount of flavor from its surroundings, gaining flavor notes which were described primarily as ‘animal’ or ‘gamey’, ‘moss’, ‘funky’, ‘pungent’, and ‘salami’. These characteristics are certainly far-flung from the creamy acidity of a freshly made cultured butter, but have been found useful in the kitchen especially with strong and pungent dishes, in a similar manner to aged ghee.

As I worked with Patrick to make this bog-butter I noticed that all he ate all day was the butter itself. This, he said, is common among butter makers. A walnut sized lump will keep one sustained all day. If we consider ancient dairy based economies, many people may have gone all day eating only butter quite frequently. Occasionally it would be consumed on an oatcake, or with a piece of meat or fish, but often on its own. In times where transhumance brought people to relatively isolated and exposed locations, time spent inside with a fire to keep warm, along with infrequent washing and living space shared with their animals, may well have meant that stronger foods became more desirable, as they had some character that stood out from the already ripe surroundings.

Taste is to a large extent culturally defined, and modern tastes have been shaped by myriad modern factors that cannot be removed from the equation. When we taste this altered butter a the 2012 Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, we had to use some imagination. As O’Laverty wrote of his own bog butter experiment in the late nineteenth century, ‘for my own taste I would prefer butter cured in the modern way, but I have no doubt that usage would confer an acquired taste’ (31).

[update by Josh 29.10.13] – This past weekend, Guillemette and I took a trip up to Floda to visit Patrik and Zandra and make some butter together. We also used it as an opportunity to check up with the bog butter. The rainy Saturday afternoon saw us following the same path through the woods, finding the rock with the missing corner, and descending off the road down into the bog. Once we located the clearing with the buried treasure, we dug up the main deposit for a taste. It is still mossy, green, and earthy – maybe it was the fact that we were also wet, a little smelly, and surrounded by the moss like the thing itself, but the butter, eaten with muddy hands in the clearing in the bog, tasted really good.

The butter is now 1 year, 6 months, 3 weeks old, and counting.

Notes

1 Caroline

Earwood, ‘Bog Butter: A Two Thousand Year History’, The Journal of Irish Archaeology, 8 (1997), 25-42.

2 Robert

Berstan et al., ‘Characterization of Bog Butter Using a Combination of Molecular and Isotropic Techniques’, Analyst, 129 (2004), 3-8.

3 L. Downey et al., ‘Bog Butter: Dating Profile and Location’, Archaeology Ireland, 75 (2006), 32-34.

4 Earwood.

5 James O’Laverty, ‘The True Reason Why the Irish Buried Their Butter in Bog Banks’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland, 2 (1892), 356-337.

6 Berstan; David MacRitchie, ‘Wooden Dish Found Lately in the Hebrides’, Archaeological Notes, Reliquary, N.S II (1896); E. Estyn Evans, ‘Bog Butter: Another Explanation’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology 3rd. ser, 10 (1947), 59-62; PRIA, vi (1858), 369-72; personal email exchange with Anders Strinnholm of Stavanger Museum of Archaeology regarding collection item S9457 – three lumps of big butter from the Stavanger area of Norway; James Williams, ‘A Sample of Bog Butter from Lachar Moss, Dunfriesshire’, Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquities Society, 3rd ser., 43 (1966), O’Laverty, ‘True Reason’. In Norway a similar practice of burying milk in peat bogs still exists as can be seen here: http://www.nrk.no/nyheter/distrikt/rogaland/jaeren/1.8061809. In Morocco butter is still preserved for long periods of time, sometimes underground, where it is known as smen.

7 ‘Terence J. Painter’, Carbohydrate Research, 338 (21 November 2003): 2777-2778.

8 Sally Pobojewski, ‘Underwater Storage Techniques Preserved Meat for Early Hunters’, The University Record, May 8 1995; retrieved 1/11/2012 from http://www.ur.umich.edu/9495/May08_95/storage.htm.

9 Traditional foods for which burying is a part of the preparation/preservation process, or for which there is evidence that this may have been the case, include: banana bread (Ethiopia, banana dough), buried eggs (China, eggs); davuke (Fiji, bread fruit); formaggio di Fossa (Italy, cheese); ghee (India, clarified butter); gravadlax (Scandinavia, salmon); gubenkraut (Austria, cabbage); hákarl (Greenland, Greenland shark); igunaq (Inuit Arctic, walrus); kiviak (Greenland, auks in a seal skin): lutefisk (Scandinavia, white fish); muktuk (Alaska, seal flipper); reindeer’s stomach (Sápmi, Sweden, stomach with contents); rue tallow (Faroe Islands & Iceland, sheep’s tallow); sealskin poke (Alaska, meat/dried fish with seal fat); smen (Morocco, clarified butter); and surmjølk/myrmjølk (Norway, milk); Many fermented foods are prepared in fully or partially buried amphoras, including wine in Armenia and soya sauce in Korea.

10 Earwood; F. J. Hunter, ‘Iron Age Hoarding in Scotland and Northern England’, Reconstructing Iron Age Societies, eds. A. Gwilt and C. Hasselgrove, Oxbow Monographs in Archaeology, Oxford: Oxbow, 1997, 71.

11 James O’Laverty, ‘Bog-butter’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1st ser., 7 (1859), 288-294.

12 Williams; Earwood.

13 Earwood.

14 O’Laverty, ‘Bog-butter’; personal communications between Professor E.C Synnott, Process Engineering Department, University College Cork, Ireland and Dr Alison Sheridon FSA Scot FSA AIFA, Head of Early Prehistory, National Museums Scotland.

15 Rev. Dr. Archibald Clerk, ‘Notes on Everything’, accessed via Dr. Alison Sheridon FSA Scot FSA AIFA, National Museum of Scotland.

16 Angus Grant, PSAS, 39 (1904-5), 246-247.

17 Niall Ó Dubhthaigh, ‘Summer Pasture in Donegal’, Folk Life, 22 (1984), 42-54.

18 Grant.

19 Earwood; Hunter; O’Laverty, ‘True Reason’.

20 Ó Dubhthaigh.

21 James Ritchie, ‘A Keg of Bog-butter from Skye’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 75 (1941), 5-22.

22 O’Laverty, ‘Bog-butter’.

23 O’Laverty, ‘Bog-butter’; O’Laverty, ‘Ture Reason’

24 Some doubts exist over the author(s) of The Irish Hudibras. O’Laverty attributes it to William Moffet in 1855 (‘True Reason’). James Farewell (1689) is written in the copy held by the British Library. www.amazon.co.uk attributes the text to ‘Multiple Contributors’.

25 O’Laverty, ‘True Reason’.

26 O’Laverty, ‘Bog-butter’; Ritchie.

27 Downey.

28 O’Laverty, ‘True Reason’.

29 PRIA, 6 (1858), 369-72.

30 PRIA, 6 (1858), 369-72.

31 O’Laverty, ‘True Reason’.