by Ben Reade.

“Smell is a potent wizard that transports you across thousands of miles and all the years you have lived”

Helen Keller (Harman, 2006)[1]

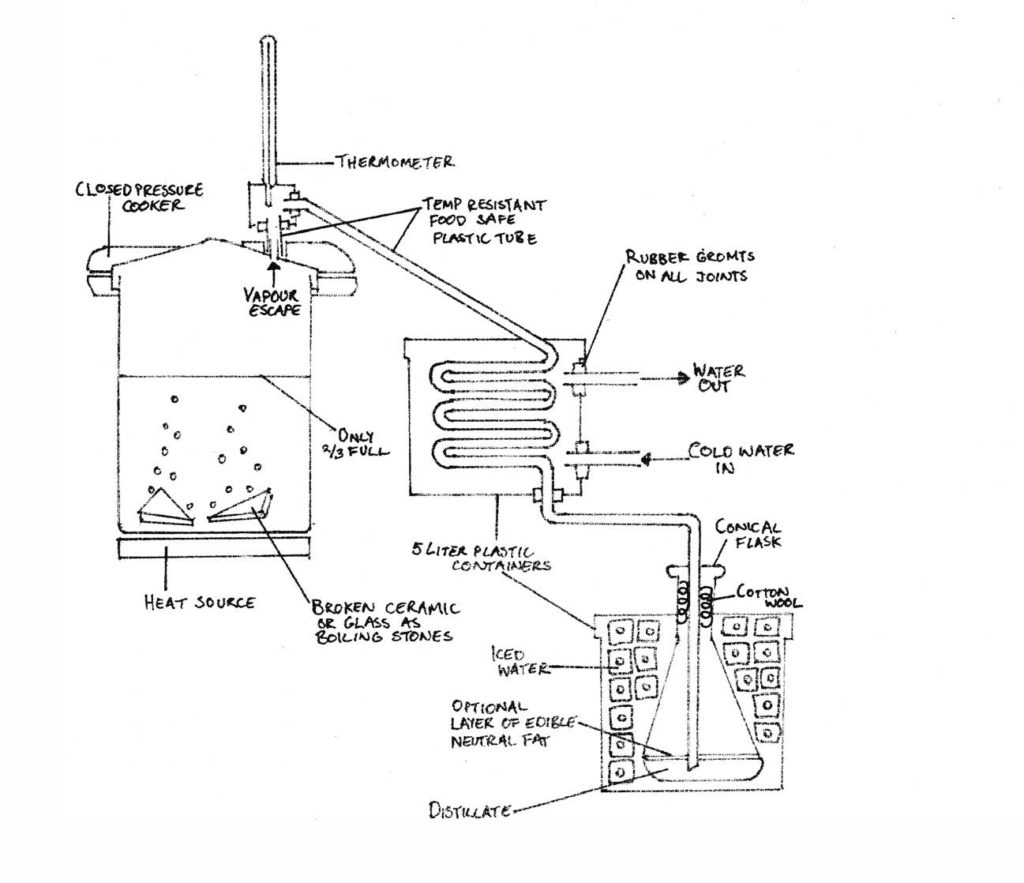

Aroma can be captured in a number of different ways. As explained in the previous post this should be taken seriously in the modern kitchen as it allows great scope for innovation. In our quest to get the most of aroma, we wanted to be able to capture the aroma which fills the room when heating ingredients. For this reason apparatus was developed as a system of aroma capturing, based on a crude distillation still. While we have breifly mentioned the aparatus in a previous post, now I’ll tell you exactly how to use it. BUT, pressure cookers and heat and vapours can be dangerous, and if you are careless, the whole contraption could blow up in your face, while I see this a pretty safe, others may not concider it as such – so dont come crying to me if it all goes wrong! The equipment is made using (mostly) standard kitchen apparatus (except some plastic tubing, small grommets and cotton wool). I hope that the ease with which this apparatus can be assembled and used will inspire artisan cooks in the house and restaurant kitchen, as well as those interested in more industrial style technique, to recognize the potential of the apparatus.

Using aroma capturing apparatus

The heat source should not be from a naked flame – induction is best. This is particularly dangerous if using alcohol or other flammable liquid, so be careful. Remember, that in most countries, distilling alcohol is illegal without license.

The broken ceramic in the pressure cooker replaces what chemists would call boiling stones. These encourage bubbling, and therefore mixing and evaporation. Use lots of small pieces, and make sure you strain them PROPERLY, if you are going to use the liquid left in the pot.

Don’t fill the pot too full, it will bubble and any particles, which enter the tube, will be pushed through to your distillate, making it cloudy or full of particles – which, depending on the application, may defeat the entire purpose.

The tube feeding from condensing chamber into reception flask should arrive at the bottom of the reception vessel.

Adding a layer of fat will capture more volatile molecules; it will however leave you with a layer of fat on your distillate – most volatile compounds are fat soluble.

When around 10 drops per minute are coming into the reception flask, then you are distilling at the correct speed. When you arrive at this speed look at the thermometer to stabilize the temperature at this point.

If you wish to arrive at this temperature again, for a second batch, then you should always check that there is condensation on the thermometer bulb, otherwise the temperature reading may be very inaccurate.

Make sure you detach the tubing before lowering the temperature inside the pot. Otherwise as the cooling lowers the pressure within the pressure cooker, all of your carefully collected distillate, will be sucked back into the pot.

To prevent the escape of volatile components, cool the distillate as fast as possible in a tightly sealed container. It can be stored frozen.

Use a craft knife to cut holes in plastic tubs and rubber grommets to make these holes water and airtight. Make sure you get grommets that fit your tubing, and tubing that fits your pressure cooker air vent.

Applications of aroma capturing apparatus

Whenever an aromatic liquid is boiled the apparatus can be used. This allows us to collect a considerable amount of different aromas, which, cooled and packed down in small vacuum bags, can be frozen until a relevant use is found.

These hydrosols may be put into spray bottles that can be sprayed over food directly before serving.

One way of keeping the aroma is to encapsulate it. Use thickeners and gelling agents to make gels, which contain the aromatic molecules. This has been done with the chicken stock recipe (see at the end of this post) making use of the gelatin in the chicken stock. This is the process used in the production of traditional Turkish delight, which use corn flour to thicken a hydrosol of (traditionally) rose.

Aromatise foods being cooked sous vide. However, the food cooked sous vide should be cooled before opening, as, again the volatile nature of these molecules does not allow for extended periods at warm temperatures without the smell escaping.

Change the collection beaker every 100 ml or so, you will notice that different fractions have different aromas and strengths. You may wish to mix them or use them for different purposes.

For aroma collection from solids, i.e. herbs, see below, for steam distillation

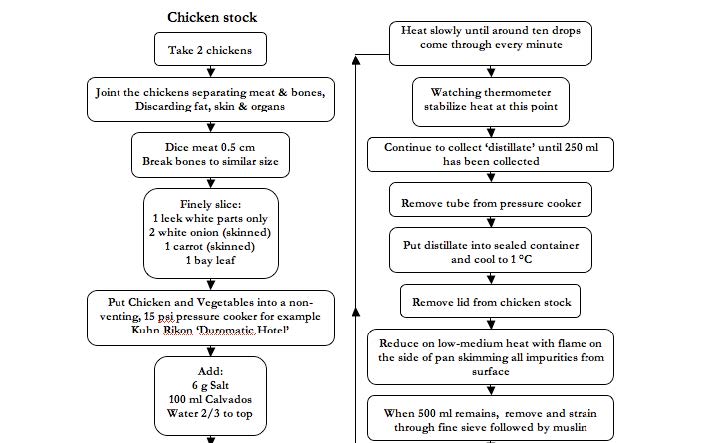

Making Chicken Stock with the apparatus

Adaptation of apparatus for ‘steam distillation’

If the aroma you wish to collect is from a solid such as a herb, use the following process to make a very rough steam distillation device. We will use the distillation of pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) as an example.

Place a metal laboratory tripod inside the pressure cooker. Set up; on top of the tripod; a divider of a steaming basket or drum sieve half way up the inside of the pressure cooker. Fill the pressure cooker with water until just below the layer of the basket.

Take the recently harvested pine, break the wood of the pine into small pieces, and blend the pine needles until they are fine. Put this all immediately on top of the sieve divider.

Close the pressure cooker and bring to the boil.

Make sure you have a large collection vessel, because you will collect considerable quantities of hydrosol and possibly a miniscule amount of essential oil.

[1] Hellen Keller (1880-1968), who was deprived of senses of audition and vision from 19 months old, was the first deaf and blind person to receive a Batchelor of Arts degree

Bibliography

Harman, L. (2006) The human relationship with fragrance, in Sell, C.S. (ed) TheChemistry of Fragrance, Royal Society of Chemistry, London, UK.

About the author

My Name is Ben Reade, I’m a chef from Edinburgh, Scotland, and for the past 3.5 years I have been studying at The University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy. For my final thesis, I came to Nordic Food Lab to research many subjects where my varied interests inerlaced with those of the Lab. The research arose out of time spent at the Nordic Food Lab between 29 September and 22 December 2011. The aim is to describe NFL’s current research to both chefs and non-specialized readers, explaining and coding the creative and scientific methodologies employed during the research at NFL, exploring their application in food experimentation and innovation. Over the next month or so I will be breaking down this thesis into manageable blog-style chunks, this is chunk 4 of around 25 I hope you find it interesting. If you want to ask me any questions directly, I’m contactable on Twitter @benreade. In general