by Josh Evans and Guillemette Barthouil

It must have been in the spring of 2013 when one of our hunters, Jesper Shytte, brought on board a beast none of us had ever worked with in the kitchen. Late April and early May, he told us, was the best time to hunt beaver, and he had brought us one, along with its castor sac and a sample of castoreum tincture he had made.

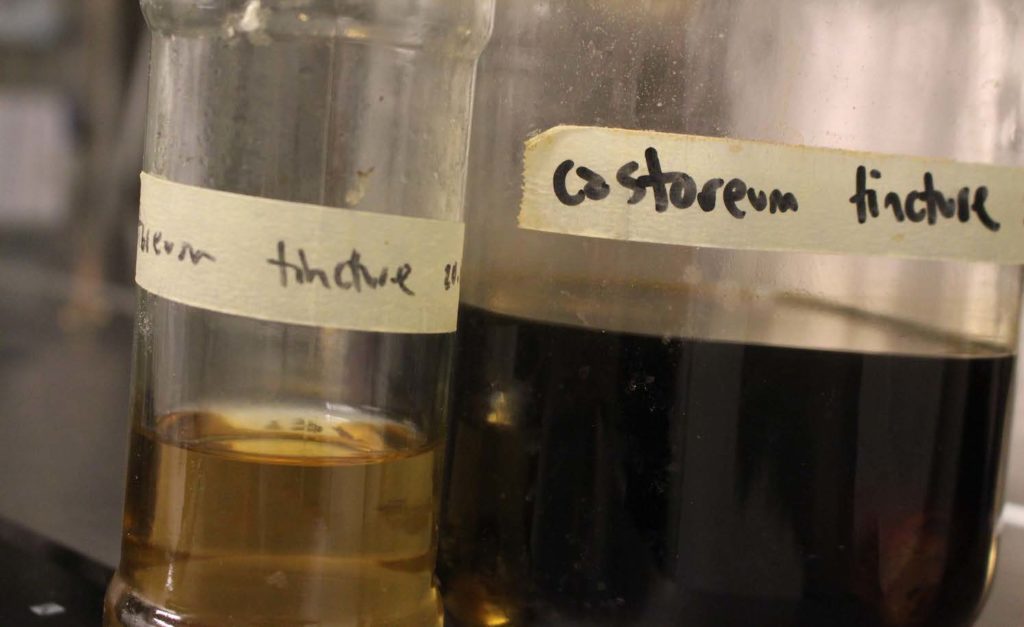

We cooked the tail for staff meal (it takes some finesse, we later learned; Jesper has since offered to show us how) after immediately popping the castor sac into 70% ethanol to make tincture our own.

Castoreum is the secretion of the castor sacs of the Eurasian and North American beaver (Castor fiber and Castor canadensis, respectively), which they mix with urine to mark their territory. Beavers have been valued for centuries in Europe and North America for their pelts, their castor sacs, and their flesh. Castoreum has a particularly long history of use. It was used as a medicine at least as early as ancient Rome and as late as the early 20th century [1], and is still used today as a perfume and food additive for its notes of leather, vanilla, smoke, and musk. In fact, beaver became so popular that by the middle of the 19th century many European populations had been trapped to near extinction [2]. They then became protected in many areas of Europe to allow the populations to recover, and now, after around 150 years, the conservation has been a great success—the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List now lists both species under the category of ‘Least Concern’. Many populations have bounced back—in some places even becoming so populous that they are crowding out other species and are beginning to have some detrimental effects on forest and riparian landscapes. They are, after all, quite efficient tree-cutters and river-dammers. Many areas of middle and northern Sweden are just such places, which is where Jesper found himself that spring, hired to help keep certain overactive beaver populations ‘in balance’ with the local ecosystem (an idea which is of course also a contestable ideological position—that humans not only have access to knowledge about this ideal, singular, and stable ‘state of balance’, but that we also have the power to orchestrate it, with or without disinterest—the ultimate neoliberal ‘Nature’ [3]).

“Wildlife emerges through ecologies of becomings, not fixed beings with movements of differing intensity, duration, and rhythm. Wildlife is discordant, with multiple stable states. It is not in any permanent balance. It is shaped by but divergent from the past, multinatural in its potential to become otherwise.”

— Jamie Lorimer, Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature

Hunting beavers is not yet allowed again in every member state of the EU, but in Sweden it is from the 1st of October to the 10th or 15th of May (the former in the south, the latter in the north). One may only hunt them with rifles [4].

Working with the beaver and its castoreum has fed into a larger ongoing conversation at the lab about humans’ roles in ecosystems, and the different ways we participate in eroding, maintaining, and contributing to biodiversity—intentionally and not. Is it possible to use responsible, ecologically-attuned hunting as a way of participating in and contributing to flourishing ecosystems? If so, how? And how can we use taste and cooking as one way to give value and respect to the creatures we hunt and to ensure, for example, that nothing goes to waste? These are not new ideas by any means, but it is surprising how far some contemporary policy and public opinion has strayed from this idea. We think it is more than time to bring it back. For a conversation between Roberto and our hunter friend David Pedersen on the role of hunting and the hunter in contemporary eco-conservation, take a listen to our NFLR podcast ‘Two white flies‘.

Since starting that first tincture in 2013, the big glass jar of alcohol sat on one of our shelves, an inscrutable specimen slowly disappearing in a darkening veil of brown. We opened it up now and then, to smell the particular smell and keep it floating in our minds.

Finally, in June 2014, Guillemette and I decided it was time for something to be done. Given we already had the castor in alcohol, it seemed perfectly natural to follow that to its logical end and make a cocktail. We have been interested in tinctures and perfumery for some time, with Ben and Justine working on different techniques, so it seemed like a great way to incorporate some of these methods of aroma extraction, like enfleurage and absolutes, into a recipe. We had also learned the beavers use castoreum to attract mates, which echoes its use in perfumery as an attractive, musky base note. At last we had an excuse to make an NFL version of Sex on the Beach.

After a few very serious experimental trials, this is what we came up with.

Sex on the Beach, NFL-style

400 ml high-quality vodka

58 ml dulse snaps (we used one made by Schumacher Brændevin)

58 ml beach rose absolute

50 ml beach rose vinegar

Castor sac tincture

Beach rose absolute

Enfleurage. Mix 50g of cocoa fat powder with 10g of fresh unblemished beach rose petals. Replace petals with fresh ones every day for one week. Then wash the fat with a small amount of 70% ethanol to obtain the absolute.

Beach rose vinegar

50g rose beach petals

450g apple balsamic vinegar

Put the ingredients together in a vacuum bag and vacuum on full seal.

Mix first four ingredients together and store in a sealed glass bottle in the freezer.

Prepare glasses by frosting in the freezer (I believe the ideal shape may be a mini-coupe). Place glasses on the counter and, using an atomiser, spray the castoreum tincture once or twice over the glasses, so the vapour settles in and on the glasses. Then fill with desired amount of cocktail, straight from the freezer. Serve immediately.

We wanted to incorporate the beach rose in two different ways, to highlight how different methods can be used to extract different registers of aroma. The absolute uses neutral fat to absorb the lipid-soluble volatile molecules, which are then dissolved out of the fat with the ethanol wash. The vinegar, on the other hand, absorbs the water-soluble volatile molecules, which are then held in the acidic solution. We also made a cordial to investigate how sugar affects aroma extraction from the rose, but didn’t end up using it—we had enough rose aroma and Guillemette and I like our cocktails spirit-forward and dry.

Aside from name, and perhaps the vodka, in no way does this recipe bear any resemblance to the actual cocktail. We’ll let the community decide if this is a good or bad thing.

Months after making this recipe, I learned that there is already a hunters’ tradition in Sweden of making snaps with the castor sac, called bäverhojt in Swedish (lit. ‘beaver shout’). There truly is nothing quite new under the sun…

Stay tuned for some further castoreum exploits…

The castor and its tincture, June 2015

References

1. British Pharmaceutical Codex, 2nd. ed. Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1911.

2. Parker & Rosell. 2003. Beaver management in Norway: a model for continental Europe?. Lutra 46(2): 223-234.

3. Lorimer, Jamie. 2012. Multinatural geographies for the Anthropocene. Progress in Human Geography 36(5): 593-612.

4. ‘Hunting in Sweden’. Handbook of Hunting in Europe, 1995. <www.jagareforbundet.se>. Published online 2005. Accessed 2015.