Researcher: Alec Borsook

Start: July 2014

End: August 2014

Overview

Sunflower seeds, among some other foods like burdock, contain chlorogenic acid, which, under alkaline conditions, transforms into a blue-green pigment. We experimented with these green sunflower seeds and their savoury, nutty, almost shrimpy flavour.

In conducting our survey of alkaline cooking methods, we noted that for certain foods, cooking at elevated pH can give rise to some dramatic changes in colour, well beyond the spectrum of browns associated with enhanced Maillard reactions.

Peanut butter cookies are an American classic, but peanuts are also among the most common food allergens in the United States, affecting around 3 million Americans—including two of my college roommates. Instead of peanut butter cookies, then, a tray of sunflower seed cookies would occasionally materialize in our kitchen. They would be just as crisp and golden-brown, their interiors chewy and moist, and yet, as often as not, we would break into the first cookie of a batch to find a core of Flubber-esque fluorescent green. This unexpected colour change, it turns out, was the result of an interaction between baking soda (an alkali) and a chemical in sunflower seeds known as chlorogenic acid.

The role of alkalis in producing this greening reaction can be explained by some of the same chemical properties that make them promoters of Maillard reactions, according to one proposed mechanism (Yabuta et al., 2001). Chlorogenic acid is an ester of quinic acid and caffeic acid, which contains a carbon ring with two adjacent hydroxyl (–OH) groups. Under alkaline conditions, protons are pulled away from these hydroxyl groups to leave two negatively charged oxygen atoms, making it easier for the molecule to be oxidized at these positions by air. The oxidized chlorogenic acid molecule can subsequently react with a primary amine, such as an amino acid, which allows the molecule to combine with yet another oxidized chlorogenic acid molecule. The product of this condensation reaction is a larger molecule, initially yellow in colour, which is rapidly oxidized to form our suspect green pigment.

Sunflower seeds were a natural choice for our initial explorations of this reaction. Hulled sunflower seeds were gently simmered in water alkalized with baking soda. The seeds quickly turned a warm, golden hue, and the mixture foamed actively—a reaction between bicarbonate and the seeds’ endogenous acids, perhaps, or the early stages of saponification. When the first traces of green were observed around the edges of the pot, the seeds were drained and left to oxidize to an intense shade of green.

The pigment produced by this reaction is not unlike the anthocyanins that give foods like red cabbage their brilliant colour, as described in our previous post on alkali cooking methods in general. Red cabbage juice can be used as a pH indicator, the anthocyanins changing from red to blue and eventually to green and yellow with increasing pH. The dark green liquid reserved from cooking green sunflower seeds follows a similar pattern, progressing through shades of blue and red with the addition of strong acid.

The just-cooked green sunflower seeds are pleasantly savoury, the vegetal, grassy notes present in the raw seeds having developed into something reminiscent of hazelnuts yet on the whole unfamiliar. When processed until smooth, the resulting green sunflower seed butter is nutty and sweet with a lingering, unmistakably shrimp-like aftertaste. While conducting this research, I encountered a dish at noma, delicate parcels of raw shrimp wrapped with steamed goosefoot leaves, which I thought remarkably evoked the seeds’ enigmatic flavour. The seeds’ unexpected shrimpy character grew even more assertive when the cooked seeds were roasted until crisp, though they lost their peculiar green hue in the process—high temperatures seem to degrade the pigment.

Chlorogenic acid is not unique to sunflower seeds; a number of foods, including coffee, peaches, and burdock root contain appreciable concentrations of the chemical. We’ve succeeded in inducing the greening reaction in burdock, which we have foraged around Copenhagen. Initial attempts at simmering burdock in alkalized water gave a product with only a modest green tint. Speculating that the natural concentration of amino acids in our burdock might be too low to produce an intense reaction, we added a pinch of dried shrimp to the pot and simmered the root until tender. And as the burdock cooled, success: it turned green as hell.

The topic of chlorogenic acid is briefly tackled in Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking, with reference to a reaction the chemical undergoes to create the “bluish-gray discoloration” sometimes encountered in cooked potatoes—an effect that can be avoided by cooking potatoes with acid (McGee 303). The greening reaction of chlorogenic acid is not mentioned directly, but it’s easy to imagine a passage explaining how sunflower seed cookies, for example, could be prevented from turning green with just a bit of acid or by using a little less baking soda. It’s true that we don’t want our sunflowers seeds to go green every time we cook with them. Still, we feel that processes such as this merit consideration as useful techniques rather than mere flaws—and not only for the surprise garnered by a dramatic colour change, but for the unexpected flavours these processes can create.

Inspired, we decided to make a dish to feature these green sunflower seeds. Beneath the science of the greening reaction, the process contains a certain poetry: from sunflower seeds exposed to alkalinity, as from the ash of a fire, arises this shock of green, this ostentatious symbol of life. And the alkalis of the sunflower seeds and the ash find their counterpoint in the deeply acidic vinegar lees. If our viili dish represented a rebirth from the ice and chill of winter, then this dessert is a kind of rebirth from fire—a recollection that whatever destruction is wrought against nature, by wildfires and other means, its seeds preserve the potential for renewed life. Plus, it’s pretty tasty.

To prepare green sunflower seeds:

Make a solution containing 15 g sodium bicarbonate per litre of water. To a medium pot, add raw, hulled sunflower seeds (250 g is plenty) and bicarbonate solution to cover, and bring the seeds to a simmer. The mixture will foam actively and develop a yellow colour. Cook the seeds until a green tint can be observed around the edges of the pot. Drain the seeds and return to the pot to cool. Their colour will gradually change from yellow to green.

Green sunflower seed ice cream

250 g green sunflower seeds

540 g water

60 g cream

100 g sugar

2 g salt

4 g iota carrageenan

1 g gypsum

Whisk together the water, sugar, salt, iota, and gypsum in a saucepan, and heat to 70ºC. Blend this mixture in a Thermomix with the green sunflower seeds and cream. Freeze in a Pacojet canister, and spin before serving.

Charcoal honeycomb

150g sugar

65g glucose syrup

25g honey

25g water

0.5 g activated charcoal, finely ground, plus more as necessary

8 g sodium bicarbonate

In a tall pot, heat the sugar, glucose, honey, activated charcoal, and water to 160ºC. The mixture will begin to smell of caramel, but it will be black in colour due to the charcoal. Whisk in the sodium bicarbonate. The mixture will expand rapidly. Pour the mixture into a parchment-lined bowl, allow to cool for five to ten minutes, and let expand and set in a vacuum chamber. Brush with additional activated charcoal powder to coat.

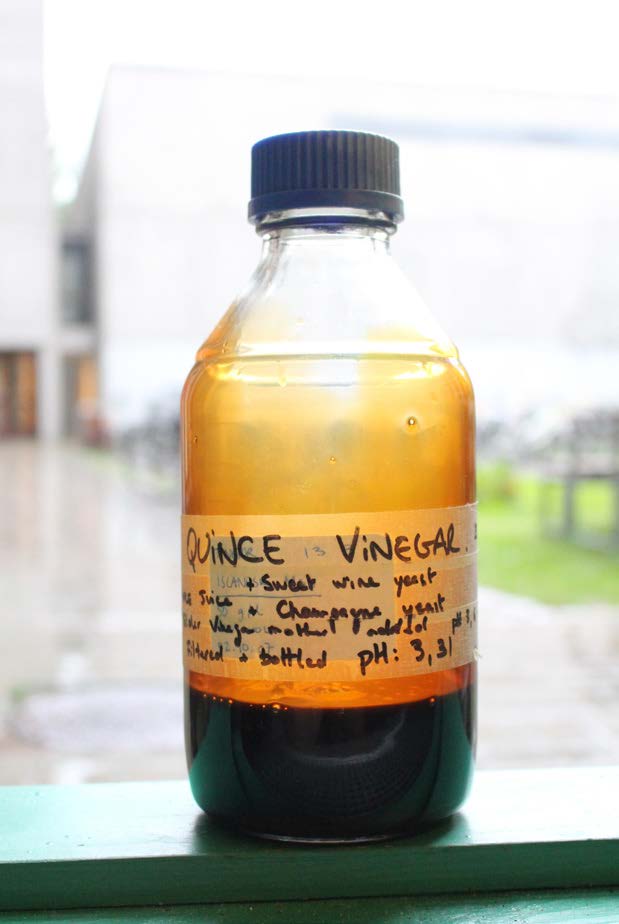

Quince vinegar lees

This was the product of inoculating the leftover quince wine from topping up our barrels of quince balsamic vinegar in winter 2013 with the robust mother from our elder vinegar of the same year. It fermented strongly and reduced down into an intense, dark brown syrup with a pH of 3.0 and brix (apparently) above 80˚ (off the charts for our poor old refractometer)—a fitting sour and astringent counterpart to the rich, nutty ice cream.

To serve

Freeze a small, round cup, ideally ceramic. Cover one side of the cup’s interior with Green Sunflower Seed Ice Cream, spread the surface with a thin layer of Quince Vinegar Lees, and top with lumps of Charcoal Honeycomb. Conceal the remaining visible ice cream with smaller pieces of honeycomb, and serve.

References

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking. New York: Scribner, 2004.

Yabuta, G., Y. Koizumi, K. Namiki, M. Hida, and M. Namiki. 2001. Structure of green pigment formed by the reaction of caffeic acid esters (or chlorogenic acid) with a primary amino compound. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 65 (10): 2121-30.