By Rachele Ellena

Since June, Nordic Food Lab has been systematically researching and cataloguing the uses of edible plants in the Nordic region, starting our efforts locally in the Copenhagen area.

We set out initially to understand the culture surrounding wild plants in the Nordic context, with a focus on current uses and historical background. In dialogue with Nordic wild flora experts and ethnobotanists, an interesting picture began to emerge. From wild plants expert and consultant Søren Espersen, we learned that the tradition of consuming wild plants in Denmark almost completely ended in the eighteenth century. Ethnobotanist Ingvar Svanberg also suggested to us that due to a general access to both public and private land in Sweden, it is more common to gather wild plants there, but he believes that all Scandinavian countries belong to the herbophobic part of Europe (herbo: herbs and phobia: fear) – a term used by Polish ethnobotanist Lukasz Luczaj to describe that part of Europe which does not generally consume wild plants. Apart from a few select plants (see table 1), there appears no extensive tradition of eating wild plants in this part of Europe.[1]

Wild foods are not completely absent from the Nordic diet, however. Instead of herbs, these countries consumed wild berries (Rubus, Vaccinium, etc.) in great quantities, particularly in the Sámi culture. Hazel nuts were also gathered, though today it is not so common as the imported nuts from Spain and Turkey are larger than the wild native varieties. And though wild mushrooms are a popular foraged food today, they were not used extensively even a hundred years ago.

A notable exception to this regional herbophobia is the long tradition of using wild aromatic plants to give fragrance to beverages: traditionally beer (see table 2), but currently more often in snaps (the Danish form of schnapps). Beer was the main drink of the Germanic and Celtic tribes, as has been recorded in ancient Roman sources.[2] Two of

the most commonly used species were bog myrtle (Myrica gale) and hops (Humulus lupulus). However, many other herbs of secondary importance have been used to flavour beer or to prepare medicinal beers. These are mentioned in old herbals and a short list of them has been compiled below in this paper (see table 2). These various flavouring agents, combined with the use of all available species of cereals, led to an incredible variety of beers.[3]

After being dismissed for many years, wild plants are now being used in some of the best restaurants in the world and people travel long distances to taste them. Plants are now celebrated, raised up to become stars of the new Nordic cuisine.[4] Based on our interviews with chefs, it is clear that they mainly use wild plants for their diverse and interesting aromas. We have compiled a comprehensive, but incomplete list of plants used for their aromas below (see table 3).

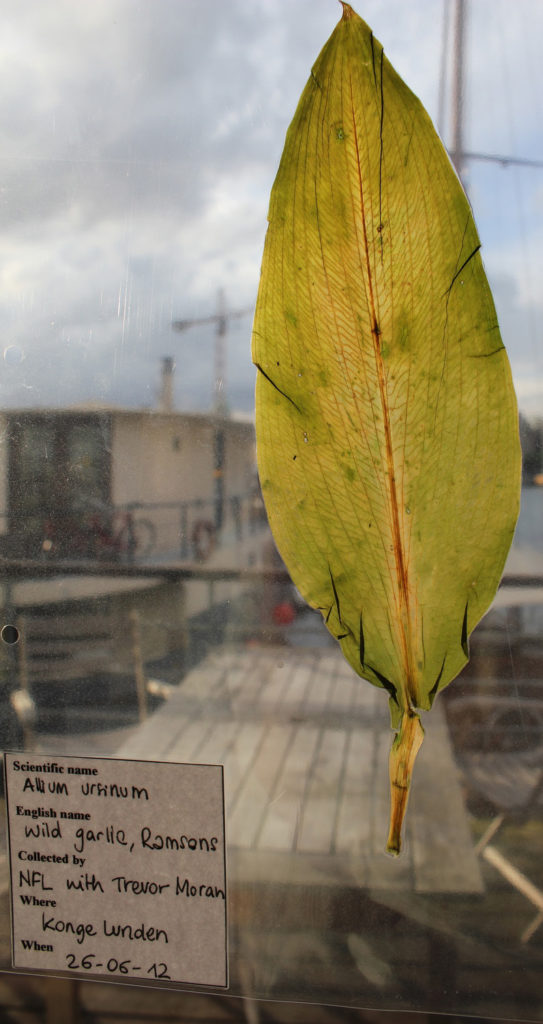

To learn more about the roots of this wild plant renaissance, we have interviewed some of the chefs working with wild plants in Denmark, in both avant-garde and more traditional cuisines. We were interested in many aspects of their craft: how their interest in wild plants began, how modern chefs use them in their dishes, and which sources of information they rely on to learn about their harvest and use. We also connected with foragers who showed us various wild edible plant species, which we collected in a herbarium here at Nordic Food Lab. Their advice has shaped our research invaluably. Professional foragers all over Europe are working to find these hidden treasures and introduce them to chefs. Both foragers and chefs play a crucial role in raising wild plants’ profile and helping to put people back in touch with their local resources.

“The experience

in the field, gathering your own ingredients […] changes the way the cooks act

in the kitchen. When you get close to

the raw materials and touch them when they are still one with nature, taste

them at the moment they let go of the soil, you learn to respect them.”

– René Redzepi in Noma: time and place in

Nordic Cuisine

The aim of our research is to create a database that will assist chefs in finding wild plants and using them in the kitchen. There is a great range of wild edible plants that grow in this climate, though many of them are still unexplored in their culinary potential. What will differentiate our database from the already vast existing literature on the subject is the information we hope to include about each plant’s tastes and aromas. We will include information about their traditional uses in Nordic cultures and update the database with results from experiments at the lab. The herbarium will be cross-referenced to the database, to help the recognition of the mentioned species. We are at the start of a long but rewarding process.

We believe that encouraging chefs to use and learn more about wild plants would help bring people into a greater awareness of the wild ingredients available in their region. This open-source database will help foragers to communicate with chefs and chefs to exchange knowledge with each other, as well as showing people that it is possible to use wild plants as vegetables, herbs, and spices. Raising people’s awareness about the tastes their environment offers will allow them to see it through different eyes: one’s knowledge makes the natural world meaningful, and this meaningfulness compels one to protect and preserve the larger system of which we are a part.

And now, a recipe. A couple of months ago we found a nice surprise on Amagerstrand, a beach of Copenhagen. As the woodruff season (Gallium odoratum) ended, we were extremely happy to find sweet clover which contains coumarin (tonka bean). chemical class, found in many plants, notably in high concentration in the benzopyrone in the chemical compound a fragrantWe started experimenting with several ice cream recipes until we found a final version made with sheep yogurt and sweet clover that convinced us.

Sweet Clover and Sheep’s Yogurt Ice Cream

4.5g dry sweet clover

175g milk

95g Danish honey

30g trimoline

450g sheep’s yogurt

23g Thick and Easy

Infuse the sweet clover in milk at 50°C for 30 minutes (we put them together under vacuum and into a temperature-controlled water bath). Strain, and dissolve the honey and trimoline into the infused milk.

Mix the sheep’s yogurt with the Thick and Easy. Add the infusion to the mix and freeze.

An Historical Overview of Eating Wild Plant Foods

Human beings have been gathering plants longer than they have been cultivating them. A complex selection process over thousands of years led to crops suitable for cultivation. Agriculture allowed our ancestors to dedicate time to activities beyond sourcing food.[5] A few selected plants are now domesticated, and it is on this small handful of species that the food security of most humans on earth relies. Ninety per cent of our food needs are covered by only twenty plants species and sixty percent of our calories come from only four plants (corn, wheat, rice, soy).[6] Over eight thousand wild plants throughout the world have been recognized as edible, but we use only a fraction of them. Most of these wild plants’ uses have been forgotten. Why is that? The reason for this lies partly in our history.

For many millennia after the invention of agriculture, people of different cultures have preserved the knowledge of using wild plants.[7] Despite having a diet based on cultivated plants, Europeans have been integrating wild plants into their diets for centuries. This traditional

knowledge was strongly threatened already during the Middle Ages.[8] During this time, the higher classes sought ways to differentiate themselves from other classes, largely by consuming goods that lower classes could not afford. With regards to food, they ate rare plants from all corners of the world. It was a sign of high social status to eat something expensive that came from far away. Meanwhile, peasants

ate easy-to-grow vegetables and wild plants because they were abundant and free to collect. Eating wild plants became a sign of low social status. When peasants moved to urban centres they did everything they could to adapt to bourgeois norms, a lifestyle modelled after European court life. After this transition, every food associated with poverty was irrevocably left behind – wild plants first and foremost.[9]

Furthermore, this process of urbanization led people to detach themselves more and more from the countryside and therefore from the skills needed to live in that environment. In the Westernized world, the supermarket became the new field. The tendency is happening all over the world, from north to south, from the farthest east to the farthest west. We have ignorantly forsaken many highly

nutritional plants that helped us to evolve on our planet over thousands of years. A prime example is stinging nettle (Urtica

dioica): ithas seven times more vitamin C than orange, as much calcium as cheese, three times more iron than spinach, and as much protein as soy bean.[10]

Despite no longer being a common skill, in many European countries collecting wild plants in spring is still a habit, or at least a hobby, especially among elder people that live in rural areas and migrants living in cities.[11] Modern ethnobotany (the scientific study of the

relationships that exist between people and plants) relies on these people to try and retain their knowledge. The use of plants by chefs of

the Nordic region shows that even when traditions falter or seem to die out, people re-discover old knowledge and re-invent uses within new paradigms – in this case, based on taste.

“Put people back in touch with wild plants and the old relationship will

revive.”

Miles Irving, in

The Forager Handbook

Table 1. List of the most common food plants traditionally and still used in Scandinavian countries

| English Name | Latin Name |

|---|---|

| Stinging Nettle | Urtica dioica |

| Sorrel | Rumex Acetosa |

| Common Wood Sorrel | Oxalis Acetosella |

| Angelica | Angelica archangelica |

| Birch | Betula sp. |

| Wild Onion | Allium scorodoprasum |

Table 2. List of secondary-importance plants used for flavouring beer

| English Name | Latin Name |

|---|---|

| Yarrow | Achillea millefolium |

| Common Bugloss | Anchusa officinalis |

| Mugwort | Artemisia vulgaris |

| Heather | Calluna vulgaris |

| Citrus | Citrus ssp. |

| Eyebright | Euphrasia sp. |

| European Beech | Fagus sylvatica |

| Fennel | Foeniculum vulgare |

| Wild Strawberry | Fragaria vesta |

| Wood Avens | Geum urbanum |

| Hyssop | Hyssopus officinalis |

| Iris | Iris germanica |

| Common Juniper | Juniperus communis |

| Wild Rosemary | Ledum palustre |

| Lavender | Lavandula angustifolia |

| Marjoram | Majorana hortensis |

| Lemon Balm | Melissa officinalis |

| Spearmint | Mentha spicata |

| Wild Marjoram | Origanum vulgare |

| Norway Spruce | Picea abies |

| Aniseed | Pimpinella anisum |

| Silverweed | Potentilla anserina |

| Wild Cherry | Prunus avium |

| Blackthorn | Prunus spinosa |

| Oak | Quercus sp. |

| Rosemary | Rosmarinus officinalis |

| Blackberry | Rubus fruticosus |

| Raspberry | Rubus idaeus |

| Sage | Salvia officinalis |

| Elder | Sambucus nigra |

| Clove | Syzygium aromaticum |

| Wild thyme | Thymus serpyllum |

| Bilberry | Vaccinium myrtillus |

Notes

1 Ingvar Svanberg, personal correspondence.

2 Charles W. Bamforth.

3 Karl-Ernst Behre, p. 2

4 Miles Irving (2009), pp. 2 – 5

5 Susan Campbell, pp. 68 – 78

6 Tor Nørretranders and Michael Pollan.

7 Andrea Pieroni, p. 1 – 13

8 Francois Couplan. MAD Symposium 2011

http://madfood.co/mad-2011/videos/francois

couplan.html

9 Massimo Montanari (1993).

10 Francois Couplan.

11 Andrea Pieroni.

Table 3. List of some of the wild plants used by Nordic chefs for their particular aromas

| English Name | Latin Name |

|---|---|

| Yarrow | Achillea millefolium |

| Ground Elder | Aegopodium podograria |

| Garlic Mustard | Alliaria petiolata |

| Wild Onion | Allium dregeanum |

| Wild Garlic/Ramson | Allium ursinum |

| Angelica | Angelica archangelica |

| Cow Parsley | Antriscus sylvestris |

| Mugwort | Artemisia vulgaris |

| Grassleaf Orache | Atriplex littoralis |

| Sea Aster | Aster tripolium |

| Field Mustard | Brassica campestris |

| Eurpoean Searocket | Cakile maritima ssp. Baltic |

| Shepherd’s Purse | Capsella Bursa-pastoris |

| Caraway | Carum carvi |

| Goosefoot | Chenopodium album |

| Chicory | Cichorium intybus |

| Sea Kale | Crambe Maritima |

| Wild Carrot | Daucus carota |

| Meadowsweet | Filipendula ulmaria |

| Fennel | Foeniculum vulgare |

| Ash | Fraxinus excelsior |

| Woodruff | Galium odoratum |

| Wood Avens | Geum urbanum |

| Sea Buckthorn | Hippophae rhamnoides |

| Juniper | Juniperus communis |

| Mallow | Malva sylvestris |

| White horehound | Marrubium vulgare |

| Pineappleweed | Matricaria matricariodes |

| Melilot/Sweet Clover | Melilotus sp. |

| Spingel | Meum athamanticum |

| Sweet cicely | Myrrhis odorata |

| Watercress | Nasturtium officinale |

| Nightlight/Evening Primrose | Oenothera elata |

| Common Wood Sorrel | Oxalis acetosella |

| Aniseed | Pimpinella anisum |

| Plantain | Plantago major |

| Ribwort Plantain | Plantago lanceolata |

| Sea Plantain | Plantago maritima |

| Common Silverweed | Potentilla anserina |

| Wild Cherry | Prunus avium |

| Blackthorn | Prunus spinosa |

| Roseroot | Rhodiola rosea |

| Ramanas rose | Rosa rugosa |

| Sorrel | Rumex acetosa |

| Sheep Sorrel | Rumex acetosella |

| Elder | Sambucus nigra |

| Hedge Mustard | Sisymbrium officinale |

| Wild Parsnip | Sium latifolium |

| European Rowan | Sorbus aucuparia |

| Swedish Whitebeam | Sorbus intermedia |

| Chickweed | Stellaria media |

| Sweet Pea | Vicia sp. |

| Tansy | Tanacetum vulgare |

| Common Dandelion | Taraxacum officinalis |

| Pennycress | Thlaspi arvense |

| Wild Thyme | Thymus serpyllum |

| Red Clover | Trifolium pratense |

| White Clover | Trifolium repens |

| Sea Arrowgrass | Triglochin maritima |

| Stinging Nettle | Urtica dioica |

| Small Nettle | Urtica urens |

| Blueberry | Vaccinium myrtillus |

| Tufted Vetch/Cow Vetch | Vicia cracca |

| Common Violet | Viola odorata |

About the author

Rachele Ellena graduated from the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Italy with a thesis in the field of ethnobotany. During her three-month internship at the Nordic Food Lab, she carried out this wild plants research project. She is now studying for her MA in Ethnobotany at the University of Kent.

Bibliography

Bamforth, Charles W. Beer is Proof God Loves Us: Reaching for the Soul of Beer and Brewing. USA: Pearson Education, 2011.

Behre, Karl-Ernst. ‘The history of beer additives in Europe – a

review’.Veget Hist Archaeobot. 8:35-48, 1999.

Campbell, Susan. ‘The Hunting and

Gathering of Wild Foods: What’s the Point? An Historical Survey’. Wild Food, Proceedings of the Oxford

Symposium on Food and Cookery. UK: Prospect Books, 2006.

Couplan, François. Guide nutritionnel des plantes sauvages et

cultivèes. France: Delachaux & Niestle.

Irving, Miles. The Forager Handbook. UK: Ebury Press, 2009.

Jensen, Steen Viggo. Vorherres Køkkenhave. Denmark: Forlaget Revling, 2009.

Kallas, John. Edible Wild Plants: Wild Food from Dirt to

Plate. USA: Gibbs Smith, 1952.

Leck Fischer, Rasmus and Dahlberg, Katja.

UKRUDT. Denmark: People’s Press,

2012.

Mabey, Richard. Food for free. Collins Gem, 1972.

Mad Symposium 2011. <http://madfood.co/mad-2011/video-2011.html>.

Montanari, Massimo. La fame e

l’abbondanza: Storia

dell’alimentazione in Europa. Italia: Laterza, 1993.

Montanari, Massimo. Il cibo come

cultura. Italia: Laterza, 2004.

Nørretranders, Tor. Vild Verden. Denmark: Tiderne Skifter, 2010.

Olsen, Anemette. Spis dit Ukrudt.

Denmark: Forlaget Skarresøhus, 2010.

Pieroni, Andrea and Vandebroek, Ina. Travelling cultures and plants. USA:

Berghahn Books, 2007.

Plants For a Future. <http://www.pfaf.org/user/default.aspx>.

Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. New York:

Penguin Group, 2006.

Redzepi, René. Noma: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine. Phaidon Press, 2010.