by Rosemary Liss.

Check out Rosemary’s first post, a slideshow of images from her summer as our artist-in-residence,

as well as our first short post on nuka from a few years back.

My interest in nukazuke stems from my more general interest in the physical relationships between bodies and food as a life-sustaining force. I was introduced to the nuka duko (or nuka pot) on my very first day working at Hex Ferments, a company that creates kombucha, kimchis and kraut in Baltimore, Maryland. This magical process inspired later artistic projects both visual and comestible.

The nuka is a perfect example of a process that was born from utilising waste. Its origin finds roots in the Edo period of Japan when the milling of rice rose in popularity. The by-product of polishing rice is the rich outer membrane also known as bran. By adding a salt brine and other inoculants from seaweed to sake, a nutrient-dense pickling bed is cultivated that, if well-tended, can pickle raw vegetables from morning to evening. This process, born from preservation and waste reduction, transmutes raw materials into a microbial-rich habitat.

I was initially drawn to the daily ritual of tending the nuka because it goes beyond food preparation and become a metaphor of life cycles. The bed is a living organism, a community of bacteria and yeast, feeding, digesting and expelling. Interpreting the nuka in one’s own environment cultivates not only a somewhat new kind of pickling machine, but also opens up new forms of living (for microbes and for humans) layered between the global and local aspects of one’s own foodshed. As I tended to our Baltimore pot—aerating the paste, removing the pickled vegetables, adding fresh ones—I began to see its possibilities for my own research and exploration. And I saw how different raw materials from Denmark might respond very differently from those found in Japan.

I found a deep connection to this daily process. When I stirred the pot my mind would slip into quiet and a sense of calm materialised; my body moved automatically with the soft sand-like paste and we become one. This past January I was a resident artist at the Vermont Studio Center. I spent a portion of the program exploring this certain intimacy. Removing the comestible component of this process by replacing the vegetables with wood and ceramic objects I created a performance piece to showcase the nuka’s meditative qualities.

While in Vermont I applied to be an intern at Nordic Food Lab. I proposed doing more research on the Nuka, but in context with the Nordic landscape. In my proposal I stated:

“Like many ferments, the Nuka is influenced by its environment, and a pot cultivated in Baltimore would produce a uniquely different mouthfeel from one in Copenhagen. My project would focus on producing a Nuka Pot connected to Denmark’s terroir as a way to study its microbial influence.“

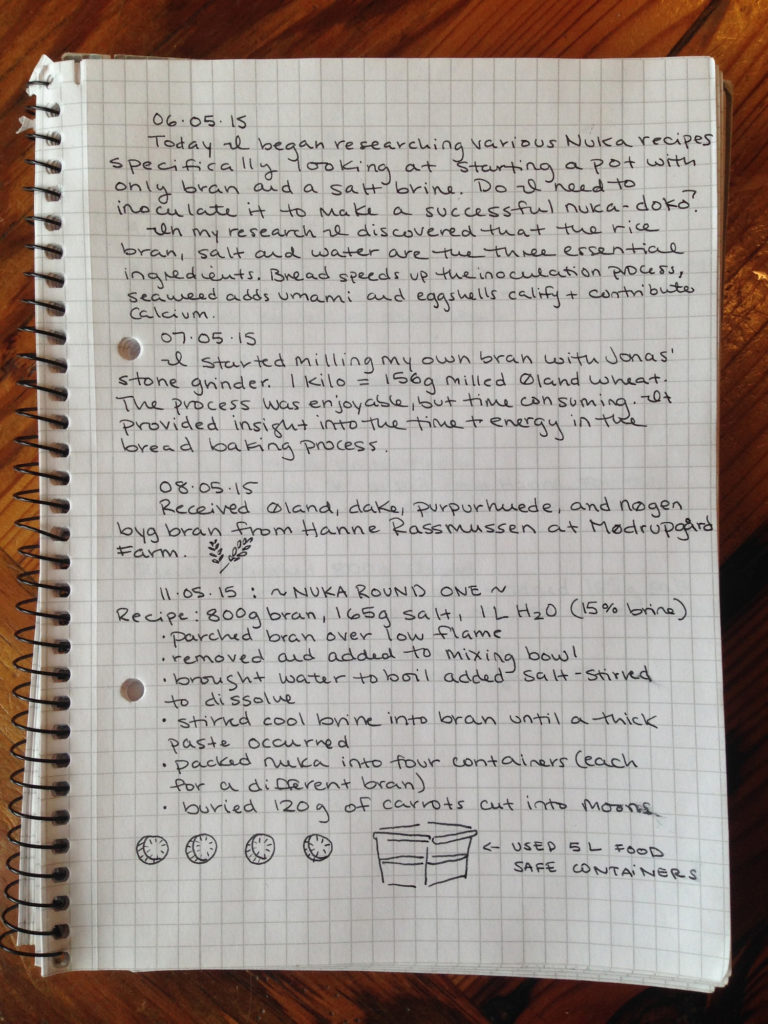

When I came to the Lab, I wanted to continue to expand on my relationship with Nuka, but in a new environment. I saw this process as a lens to study the Nordic terrain—I would recontextualise the process within the structure of my available materials. It was a starting point to begin to understand the importance of using what a particular ecosystem provides. In my notes I wrote:

“I will begin my research studying the ability of a variety of traditional Nordic grains to find a good alternative to rice bran. I will create multiple nuka pots in 5 L containers with the controls being set for the same amount of bran and salt in each pot and only carrots as the pickling object. Once I have found the ideal bran, I will broaden my research to explore a variety of inoculates including: seaweed, beer, and miso. I will explore whether these ingredients are necessary to help the nuka ‘bed’ ferment and protect from spoilage. When I have found the most ideal flavor profile and combination of ingredients I would like to play with burying various vegetables, fruits and proteins and see which ingredients produce the best nuka pickles.”

Specific requirements for the nuka:

1. The pickled vegetables have a complex flavour, tangy and aromatic from the pickling medium, with a crisp yet yielding texture;

2. The pickling bed has good consistency: not too moist nor too dry (ideally the texture of wet sand);

3. The pickling bed can make good pickles in 6-12 hours.

I did research on four different heritage grains. My colleague Jonas, our team sourdough baker, introduced me to grains I had never heard of, like Øland and Dacke wheats. He taught me how to mill my own flour, removing the hull or husk of the grain. I loved using the small stone grinder to turn whole kernels into flour. This process was beneficial both to Jonas and to me. As the wheat was milled and sifted, he was left with fresh flour for baking, and I was left with its by-product, the bran, for my nuka pots. It was a perfect relationship, especially in a space that focuses on finding latent potential in all kinds of raw materials and utilising what might otherwise be seen as waste.

Nordic Food Lab is a hive of interdisciplinary learning, but it is still a laboratory. And when you do research-based projects to try to generate knowledge it is vital to set up controlled experiments. Below are my notes from my first experiment.

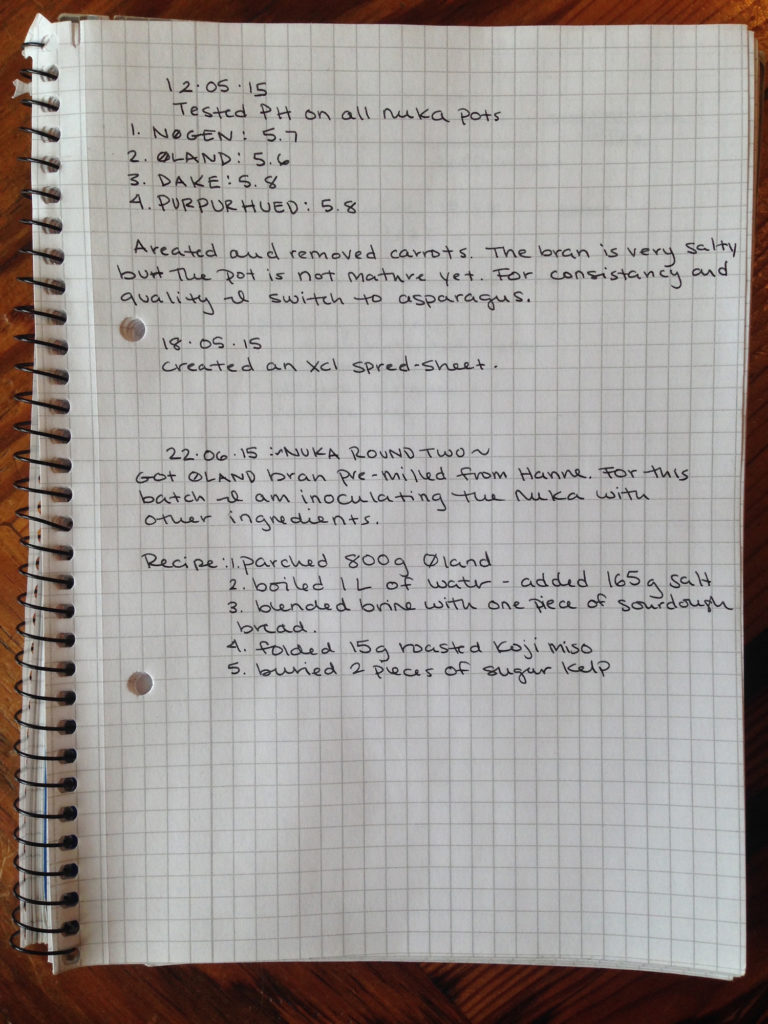

It took a while for the beds to ferment and the salt content remained high. Every day I would aerate the nuka bins and remove the pickled carrots. I tested the “soils’” pH content and added fresh veggies. The nuka ranged from dry to sticky and the four types of bran had a fluffier consistency than the rice bran I was used to.

Obtaining organic, local carrots was not as easy as I had hoped, so I switched my control substrate to asparagus, which is bountiful in the summer months. When pickled, the tough skin would soften and become prune-like as the membrane began to break down. The asparagus kept a nice crunch with a burst of briny juice ranging from sour to sweet. There were slight variations in flavour and texture depending on the bran, but it did not obtain the complexity of flavour I was used to with a traditional rice bran nuka.

Yet still from these trials I had discovered that the Øland was the most suitable bran. Focusing on one pot for my second experiment, I got a much larger batch of pre-milled Øland. For this round I inoculated the batch with pieces of sourdough baked in the lab, sugar kelp, eggshells, and roasted koji miso. The bran fermented more quickly and the pH began to drop. Immediately the flavours were more intense and a complex umami taste developed. The bed, however, remained fluffier than my first trial batch of Øland bran and began to smell of ethanol. For my first batch, I milled the Øland wheat myself; for the second batch, I used bran from wheat that had been milled at the farm. The second batch was fluffier and did not stick together well, which I believe might have come from the two brans having different final compositions—the second batch bran had more efficiently removed the husk resulting in its particular certain texture, while my own bran seemed to have a higher concentration of flour remaining, which provided more texture to the paste and probably was also facilitating the growth of metabolising yeast and LAB.

By the beginning of July I had eaten so many pieces of asparagus that they began to blend together and my tongue had difficulty discerning between the nuances in nuka pots and fermentation times. The pH did continue to go down, but so did my energy level. I felt uninspired and the act of churning the pot everyday became a chore. I started to get jealous of colleagues who were experimenting with a variety of dishes and the excitement that followed each success and failure.

I continued to aerate, remove and replace vegetables in the new nuka for another week. The pH went down slightly, but the nuka bed did not yield tasty results and the bran remained fluffy, lacking the pasty, sandy consistency of the rice bran. After some deliberation, I put the project to bed and composted the nuka.

I did find that Øland wheat was a suitable alternative, but suitable doesn’t necessarily mean exciting or delicious. Ultimately, none of the grains I tried really compared to the flavour and texture of rice bran. I also began to understand that the purpose of the lab isn’t to take a traditional process and make it Nordic, but to find something in one’s environment and cultivate it through experimentation until you create something that is delicious unto itself. It was about exploration and playfulness, feeling alive and coming into that space everyday to share with my colleagues interesting tastes and new combinations of ingredients and dishes. I found the routine and body connection in other ways. Feeding sourdough and making rye bread, gutting fish, and processing bee larvae. No longer was I second guessing my role and I began to play.

While my nuka was a failure, it was also a gift. I had to struggle through it to find meaning and context for other projects. I would hurry though my own research so I could have more time talking tempe with Bernat or learn how to make the perfect tortilla with Santiago. Meanwhile a kombucha SCOBY I had brought all the way across the Atlantic had settled nicely into its new environment and multiplied.

At that time I was thinking about the intersection between eating and disgust. Bernat had just presented some trials from his tempe project at a conference put on by the Asian Dynamics Initiative at the University of Copenhagen, entitled ‘Food, Feeding, and Eating in and out of Asia’. The team was surprised to discover the intensity of the audience’s reactions. Those that had grown up eating traditional tempe found this new softer, chewier and mildly acidic cousin revolting (more info in part 2 of Bernat’s tempe research results). It brought up many questions about how cultural perception creates a framework for taste. With these discussions in mind I started to experiment with the SCOBY itself as an edible substrate, playing with similar themes. My adventures cooking with kombucha began and my nuka experiments came to an end.

But really it’s not the end. The work becomes part of a greater rhizome of material generated by the lab; these small failures are part of a larger experience. We are not specialists, were are enthusiasts. Most of us don’t come from long generations of singular producers or craftspeople. We are looking around at the world with open minds and excited hearts and we are making a big mess and out of this mess we find new and experimental ways to think about what growing, preparing and consuming food means to us.