by Ben Reade.

As part of Nordic Food Lab’s insect project, we are lucky enough to work alongside Jørgen Eilenberg and Annette Bruun Jensen. These clever folks are specialists in insect pathology at Copenhagen University and they have been helping us figure out some complicated aspects of insect eating. So, since starting our research they have begun to uncover some details about a parasite that may or may not be a problem for humans. So although we don’t have very much information at this point, we wanted to share what we had in this mini-post to keep everyone up to date. Here is a brief excerpt from Annette:

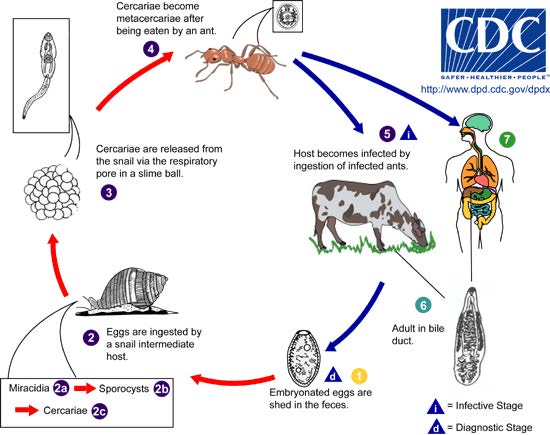

“The Lancet liver fluke, Dicrocoelium dendriticum, is a trematode parasite that inhibits the bile duct of its terminal host, normally a grazing animal. To fulfil its life cycle, it needs to complete its developmental stages in intermediate hosts: first terrestrial snails and then ants. In Denmark we know that the red wood ant, Formica rufa, is infected by the Lancet liver fluke. Ants infected with fluke cercariae don’t usually die from the infection, but as a ‘body-snatcher’ the parasite causes a change in the ant’s behaviour: at daytime, they climb up vegetation to some elevated position and bite the leaf or grass blade with their mandibles. The parasite-manipulated ants then have a much higher chance of being eaten by the fluke’s terminal host.

“Human infections are rare because it comes along with ingestion of a live infected ant. So if you want to taste ants foraged from nature, don’t eat them raw. This rule is recommended not only for ants, but for other insects in general, as we don’t always know what other parasites they may be carriers for.

“As for eating live or raw insects foraged from nature, it should only be done on insects that have been researched, either by researchers, or by locals who have explored the eventual risks in their traditional cuisines.”

So from what Annette is saying, it is best to steer clear of most raw wild insects, especially if there is no existing widespread tradition of eating them. Now, she is a scientist and we (some of us) are cooks. We recognise that scientists recommend a whole host of things which chefs like to disregard, like, for example, deep-freezing of fish before making sashimi (deep freezing almost certainly kills the ant fluke as well). We also recognise that ignoring such processes is often not out of negligence but out of a desire to maximise sensory experience of the product, and it should to some extent be up to the well-informed individual what they choose to do. Josh and I for example, well in the knowledge of this, have been eating a bunch of raw insects on our field work, because it is most important to try everything – and often they are part of an existing culinary tradition. So, we supply with the facts, you choose to do with them as you will.