posted by Ana Caballero & Josh Evans

Back in the early summer we had a guest: Rick Stepp, an ethnobiologist from University of Florida. He was in town and came by to tell us all about his current work on the bio- and cultural diversity of tea in Yunnan Province, China. But he’s also a extremely knowledgable about other plants, and, as it happens a keen brewer. This seemed an ideal opportunity to head out to some green spaces and collect ingredients for some wild ingredients we could make beer with. We gathered a small group and went for a good ol’ forage.

We asked Trevor Moran, ex-long-time Product Sous-Chef and master forager at noma, to come with and lead the way to some favourite foraging spots. We were keen on collecting as many plants for beer-making as possible, but the further we got into the woods, the more and more we realized how keen we were on one plant in particular: clove root (Geum urbanum).

Ana took some footage of the expedition. Check out the video below.

Some of the plants we found:

Dead nettles

Chickweed

Blackberries

Beech leaves

Pine shoots

Woodruff

Ground elder

Wood sorrel

and, of course Wood avens.

As Trevor mentions, the great irony of plants like Wood avens is that for centuries, Europeans have been looking everywhere else in the world for ‘exotic’, spiced flavours, when we have also had our own spices in our forests, fields, marshes and mountains. We have fought wars for control of spice trade routes and monopolies, and for much of human history, spices have been worth many times their weight in silver and gold, from 400BC Han Dynasty China, to Pliny the Elder’s Ancient Rome, and onward.

For cloves in particular, the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French spent much of the 15th century during the Age of Exploration vying for control of this lucrative industry, based in the Mollucca island group in Indonesia. Did they not know about Geum urbanum ? That is unlikely. Or was it because it was so close to home that it held less value?

After harvesting some Wood avens, Rick talks about allelopathic chemicals as why he thinks the roots might have a stronger smell the further they grow from the rhizome.

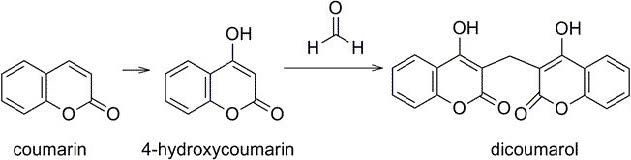

As Ben and Trevor walk back through the woods after the successful forage, they talk about coumarin as the source of the sweet, fresh-hay smell in woodruff, sweet clover, and tonka bean, and its ability to be synthesised into potentially dangerous anti-coagulant dicoumarol by certain fungi, such as Penicillium jenseni. This was discovered when cows began exhibiting signs of internal bleeding after ingesting sweet clover (Melilotus spp.) hay that had been left wet and gone mouldy. After being identified in 1940, dicoumarol became the pharmaceutical prototype for the class of 4-hydroxycoumarin derivative anticoagulant drugs. Still, a reason to not let your coumarin-bearing plants to go mouldy.

Bibliography

Bellis, D.M. et al. “The Biosynthesis of Dicoumarol”. Biochem J. 1967 April; 103(1): 202–206. 18 August 2013. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1270385/>.

“Cloves”. The Epicentre. 18 August 2013. <http://theepicentre.com/spice/cloves/>.

Hays, Jeffrey. “Cloves, Cinnamon, Mace and Nutmeg: The Spice Island Spices.” Facts and Details . March 2011. 18 August 2013. <http://factsanddetails.com/world.php?itemid=1610&>.

“History of Spices”. Indianetzone . 18 August 2013. <http://indianfood.indianetzone.com/spices/1/history_spices.htm>.

Nicole Kresge, Robert D. Simoni and Robert L. Hill (2005-02-25). “Sweet clover disease and warfarin review”. Jbc.org. Retrieved 2012-09-26.

Pliny the Elder. The Natural History . trans. Bostock, John and Riley, H.T. Perseus Digital Library. 17 June 2013. 18 August 2013. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137>.