posted by Guillemette Barthouil, recipe development for our Pestival menu Stories on limitation.

In a contemporary context of infinite possibilities we look for constraints, both to challenge our creativity and give meaning to our action. Following the seasons, exploring a territory, collaborating with crazy producers… looking into these constructive interactions to push you to do better.

Blossoms are out in the Denmark and, like us, bees are flying around in search of fresh and tasty food. Having lived on their own honey during winter, they are now looking for flower nectar, pollen, tree sap and resin to produce the honey, bee bread, propolis, royal jelly [1] and beeswax necessary for the hive community.

With the exception of honey, bee products are mainly considered medicinal. We eat them not because they are good but because they are good for us. Yet the bee hive produces a wide palette of fascinating flavours, which is rather incredible considering they all come from the same small house and are produced by the same animal.

So talking about limitation, I spent a few weeks trying to develop a dessert based only on the beehive. We served this dish as part of our menu for the NFL talk and tasting workshop at Pestival in London, entitled ‘Exploring the Deliciousness of Insects’.

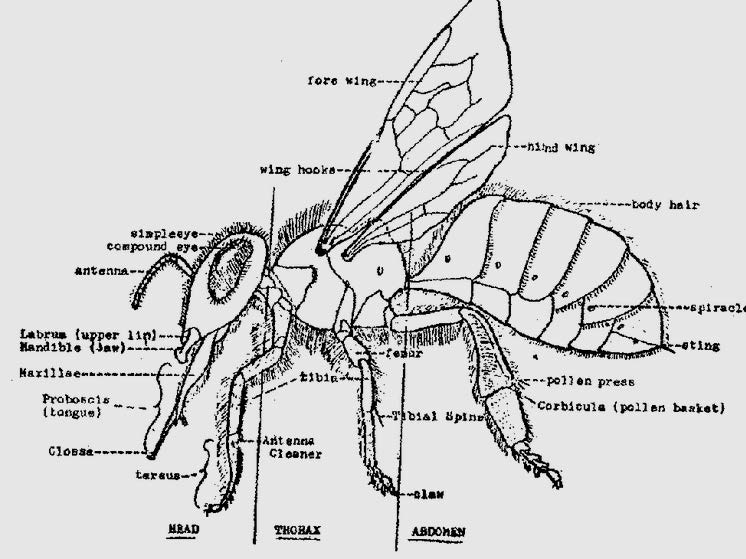

Beeswax is a natural wax produced by worker bees of the genus Apis. As the main building material it makes everything possible in the hive. In the hexagonal wax cells, bees store honey, pollen and nest their brood [2]. Bees secrete wax only while bringing nectar and pollen to the hive. The eight wax-producing glands are located on four abdominal spiracles. Produced by the glands, the wax is then seeped to the outside of the mirrors and cooled in contact with the air, forming a thin and white layer. It becomes progressively more yellow or brown by the incorporation of pollen oils and propolis – certainly a complex taste, though a less pure and consistent one. We have therefore decided to cook with purified and bleached beeswax, which beekeepers use to make honeycomb foundation.

Beeswax is mainly composed of esters of fatty acids and different long chain alcohols. To extract as much flavour as possible it seemed appropriate to infuse in a fatty solution like cream. And what to do with cream… ice cream, no? But then comes the difficult part: what is the best infusion temperature and time? After a few weeks of research (it has been a challenge) it seems that blending cold- and hot-infused creams gives the best result (at least for ice cream). The cold-infused cream for 18h at 4°C, enhances the subtle floral honey-like, nectary flavours while the hot infusion for 1h at 80°C [3] brings more structure to the ice cream with its resinous, earthy and astringent notes.

Beeswax ice cream recipe (for 1 paco container – 12 servings)

– 70 g of beeswax

– 400 g of cream 38% fat

– 255 g of cow’s milk 3.5% fat

– 200 g of cow’s milk yogurt

– 93 g of trimoline

– 3 g of guar gum

– 1.3 g of salt

The day before :

Freeze, grind and cold-infuse 20 g of beeswax into 50 g of cream. Leave at 4°C for 18h.

Production day :

Freeze, grind and hot-infuse 50 g of beeswax into 350 g of cream. Put into water bath at 80°C for 1h.

Meanwhile, pass the cold infusion through a superbag. Weigh 30 g and reserve the cream. Weigh all the other ingredients. Melt the trimoline (should not be hot) and mix it with the milk, yogurt, guar and salt.

When the hot infusion is done, put it in the blast freezer until the cream reaches body temperature. The beeswax should solidify in a block – throw it away and pass the rest of the cream through a superbag. Weigh 270 g of the hot-infused cream and add the 30 g of cold-infused cream. Blend with the rest of the ingredients in a pacojet container and freeze.

Wait until it’s frozen, paco and most importanty taste it!

Bee bread is a fermented staple food of bees. Honey bees obtain two things from flowers: nectar for honey production and pollen. So why not to bring them together in a sauce? We all know plant pollen, a source of energy and allergy – and an essential part of the bees’ diet as their primary source of protein. Yet it is a seasonal product, so the bees preserve it themselves – and what else but to ferment it! Lacto-fermentation [4] is hardly the sole domain of humans. Bees pack the pollen into a beeswax cell with their head. During the packing, the bees mix the pollen with nectar, enzymes and bacteria that will transform the plant pollen into bee pollen. The resulting material is more nutritious than the untreated pollen, both for the bees and for us. It also happen to taste fantastic. Flowery top notes and a light bitterness persist, with a slight sourness and peach stone flavours from the fermentation and moist, dense yet powdery texture that coats your mouth. A rich food that could be balanced with a refreshing honey Kombucha.

Honey kombucha sauce recipe (for 12 servings)

– 190 g of honey Kombucha

– 10 g of beebread

– Agar agar

Weigh and mix the kombucha [5] and pollen. Stir.

Cold-infuse at 4°C for 18h (stirring occasionally, except for the last couple of hours). At the end the pollen should have sedimented. Pass the mixture through a superbag.

Weigh and add 0.6% of Agar.

Bring to the boil, wait for 30 s and let it cool down until it becomes a gel. Blitz it until smooth.

Propolis can remind one of a food that is better for you than it tastes. However, it has a fantastic aroma. This ‘bee glue’ sticks the hive together, protects the colony from foreign objects and inhibits microbial growth. A multifunctional product, it is made from resins from tree buds and sap, and composed of phenolic compounds (58%), beeswax (24%), lipids (8%), flavonoids (6%) and terpenes (0.5%) [6].

The beeswaxy and fatty components of the propolis are not necessary for the dish, since they are already there in the ice cream. To extract polyphenols and terpenes we made a tincture, macerating 10% of propolis powder into 60% ethanol for at least one week. This gave us a strongly resinous, nectary, minty solution with a good bitter taste – an astringent concentrate that we use to spray on the sweet honey crisps.

Honey crisps recipe

– Crumiel (freeze-dried honey and maltodextrin)

– Propolis tincture (10% of propolis in 60% ethanol infused for a minimum of one week)

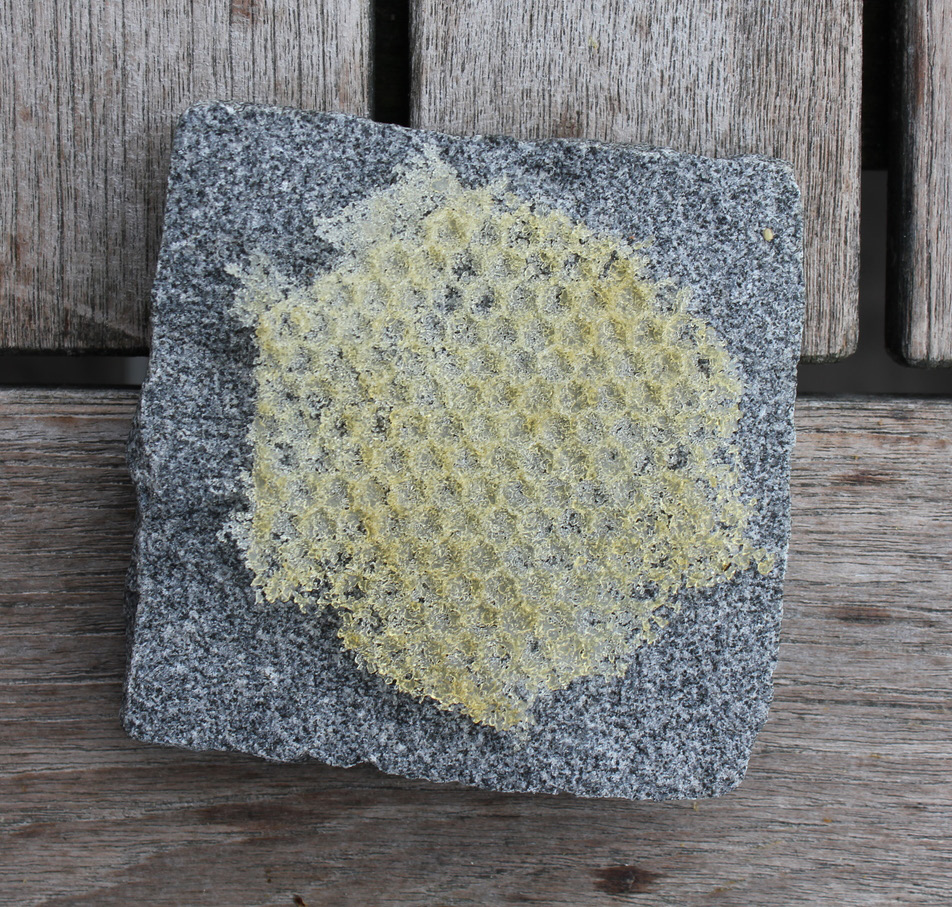

Dust a thin layer of crumiel on the moulds. To reproduce the beautiful hexagonal beeswax shape, we made our own moulds by pressing beeswax into silicon. Put in the oven at 150°C for 3min. Remove from oven, press beneath a silicon sheet and return to the oven for 30s.

Take out, wait until the caramel has reached body temperature and peel the crisps carefully from the mould.

Just before eating spray with some propolis tincture.

As you may have noticed, infusion is a recurrent technique through these recipes. Dealing with food that has been processed by bees already, the aim for this dessert was to alter these products as little as possible. Infusing the ingredients in cream, alcohol or water according to the composition of the substrate has allowed us to extract flavours to reintegrate them in our edible beehive.

Of course, in the end it must taste good – otherwise this all becomes just storytelling.

[1] We have not managed to integrate royal jelly in this dish, though this is worth further investigation, especially considering its umami component.

[2] Thank you to Annette Bruun Jensen, Associate professor at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, for the precious information about bee’s life cycle.

[3] 80°C has been prefered since the beeswax melting point is around 63°C, depending on its purity, and its discoloration occurs above 85°C.

[4] Vasquez, A ; Olofsson, T. The lactic acid bacteria involved in the production of bee pollen and bee bread. Journal of Apicultural Research,vol 48, 3, 189-195

[5] The sugar content and sourness of the sauce depends on the development stage of the Kombucha. For futher details have a look at our post on Kombucha.

[6] Farooqui, T; Farooqui, AA (2012). “Beneficial effects of propolis on human health and neurological diseases”. Frontiers in bioscience (Elite edition) 4: 779–93